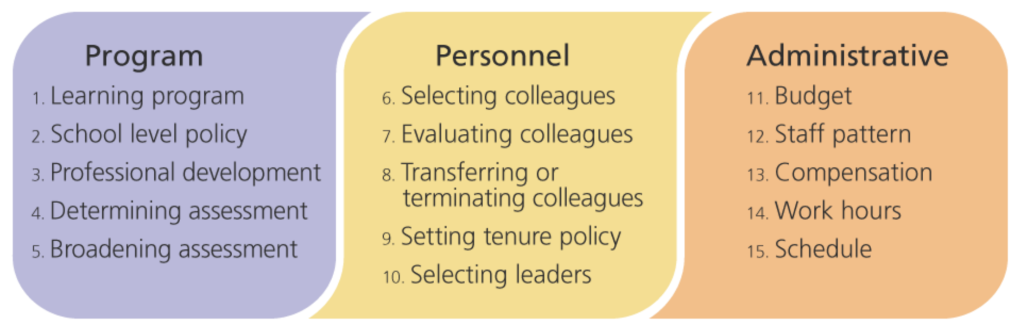

A core component of the teacher-powered model is that educator teams have secured autonomy to—collectively, as a team—make decisions in at least one of 15 areas of autonomy. Those areas are summarized in the figure below, and detailed in this publication.

In order to secure autonomy in these areas, teams use a number of different autonomy arrangements, which we also track in this inventory. Those arrangements are summarized below.

Autonomy Arrangements

Chartered school contract and/or chartered school bylaws

States, counties, and school districts authorized chartered school contracts knowing that the contracts were written to formally authorize teacher autonomy. For some chartered schools autonomy is not granted via the contract but is instead made formal via the schools’ governing bylaws.

Contract between chartered school board and teacher professional partnership

EdVisions Cooperative, established in 1994, enters into contracts with chartered school boards across the state of Minnesota, accepting accountability for school success in exchange for its teacher-members’ authority to make decisions about the school. With their authority the teachers determine curriculum, set the budget, choose the level of technology available to students, determine their own salaries, select their colleagues, monitor performance, and sometimes hire administrators to work for them.

Innovative Public Schools Act

The Howard C. Reiche Community School in Portland, Maine initially converted to a teacher-powered governance structure in July of 2011, after receiving approval from the Portland Public School’s Board of Education. The school board approved a school proposal that outlined their proposed governance structure: the school can have a team of lead teachers (instead of a principal), who will represent the school on the district’s Administrative Team. The site teachers can also select the lead teachers. Reiche teachers follow district policy and collective bargaining in the areas of teacher evaluation, professional development, learning program, school policy, and school site budget. The allocation of discretionary funds is determined by the lead teachers with input from the staff and leadership team.

Instrumentality charter contract

Since 2001, the Milwaukee Public School board has authorized instrumentality chartered schools that it knows will be run by teacher cooperatives. Much of the autonomy for the teacher cooperatives is arranged via the charter contract between the school board and the school. Before the end of collective bargaining in Wisconsin in 2011, teachers in these cooperatives remained employees of the district and members of the union. Schools also had a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the district and union local that provided waivers from aspects of the collective bargaining agreement. However, with the end of collective bargaining in the state, these MOUs are no longer necessary.

MOU between school, district, and union local + Waiver from state statute

The Math and Science Leadership Academy (MSLA) in Denver, which opened in 2009, has an MOU with the teachers union, through the Denver Public Schools school board, to have a lead teacher instead of a principal. Denver Public Schools also, specifically for MSLA, requested and received a waiver from the state of Colorado so the lead teacher has autonomy to manage the school, deal with suspensions, and do teacher evaluations. De facto the lead teacher approves decisions made collectively by MSLA teachers. This model was replicated by the Denver Green School in 2010.

Partnership model with Empower Schools

Supported by Empower Schools, districts create empowered zones within their boundaries for some schools to have autonomy in budget, staffing, scheduling, curriculum, and culture. Many of these teams become teacher-powered schools, sharing the autonomy amongst the collective teams. These zones are managed by a Partnership Team rather than the district office and are accountable to a community-led board. The board acts as an advisory council.

Pilot school agreements (Boston and Los Angeles)

In 1994, Boston Public Schools designed “pilot schools” in an effort to retain teachers and students after the Massachusetts legislature passed a state chartering law in 1993. Under the pilot agreement, the BPS Superintendent delegates authority to pilot schools’ governing boards to try new and different means of improving teaching and learning in order to better serve at-risk urban students. The potential exists for the boards to informally transfer that decision-making authority to the group of teachers at the school. Some boards have done this, to varying degrees.

PROSE Agreement

PROSE (Progressive Redesign Opportunity Schools for Excellence) was negotiated into the 2014 teachers’ contract by the United Federation of Teachers (UFT) and the New York City Department of Education (DOE) as a way for schools that had a history of collaborative management and innovation to have more freedom to achieve their goals. The idea came from union leaders seeing that teachers had creative ideas in their schools, but teacher teams needed an opportunity to share those within and across schools and more space to experiment with new ideas.

Provision in collective bargaining agreement between district and local union

In 2009, teachers in Hughes STEM High School in Cincinnati, Ohio secured collective autonomy to run an existing school via the Instructional Leadership Team (ILT) structure negotiated in the collective bargaining agreement between Cincinnati School Board and Cincinnati Federation of Teachers. Two-thirds to three-quarters of ILT members are teachers, and other team members include 2 classified employees, 2 parents, and the site principal. The ILT authority is broad, as nearly anything that affects instruction can be voted up or down by that body, and the principal does not have veto power. The ILT structure is available to all schools in the Cincinnati Public School district.

School Based Option

States, counties, and school districts authorized chartered school contracts knowing that the contracts were written to formally authorize teacher autonomy. For some chartered schools autonomy is not granted via the contract but is instead made formal via the schools’ governing bylaws.

Site-governance agreement between district school board and district school

In 2009, with support from Education Evolving and the Minneapolis Federation of Teachers the Minnesota Legislature passed the Site-Governed Schools law, allowing for the creation of schools inside districts that enjoy the same autonomy and exemption from state regulation as chartered schools. San Francisco Community School has similar autonomy through their Small School By Design agreement with San Francisco Unified School District. In Los Angeles, the Woodland Hills Academy has been operating under the similarly organized Expanded School-Based Management Model.

The goodwill of superintendent, principal or governing board (informal)

None of the schools in this group have any formal agreement granting the teachers authority to make decisions, although teachers working in them seem comfortable that their authority is secure. Teachers’ authority rests on the goodwill of a superintendent, principal, and/or governing board.

Unknown arrangements

Education Evolving does not yet know for sure whether or how a number of schools included on our list offer decision-making authority to teachers. They are included on our list because we have heard about them from various sources, including the press. We are still in the process of connecting with teachers in these schools to learn more about their arrangements.

Independent Schools

At Teacher-Powered Schools we focus on supporting public schools in the district and charter sectors. We know that there are several models of Independent Schools (private) that also use shared leadership governance models. When we come across Independent School models that might be beneficial to Teacher-Powered Teams we include them here with a note that they are private schools. The context and environments of Independent Schools vary widely, and while some of their innovations may not be transferable to the public school setting, others may be valuable to our network.

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP