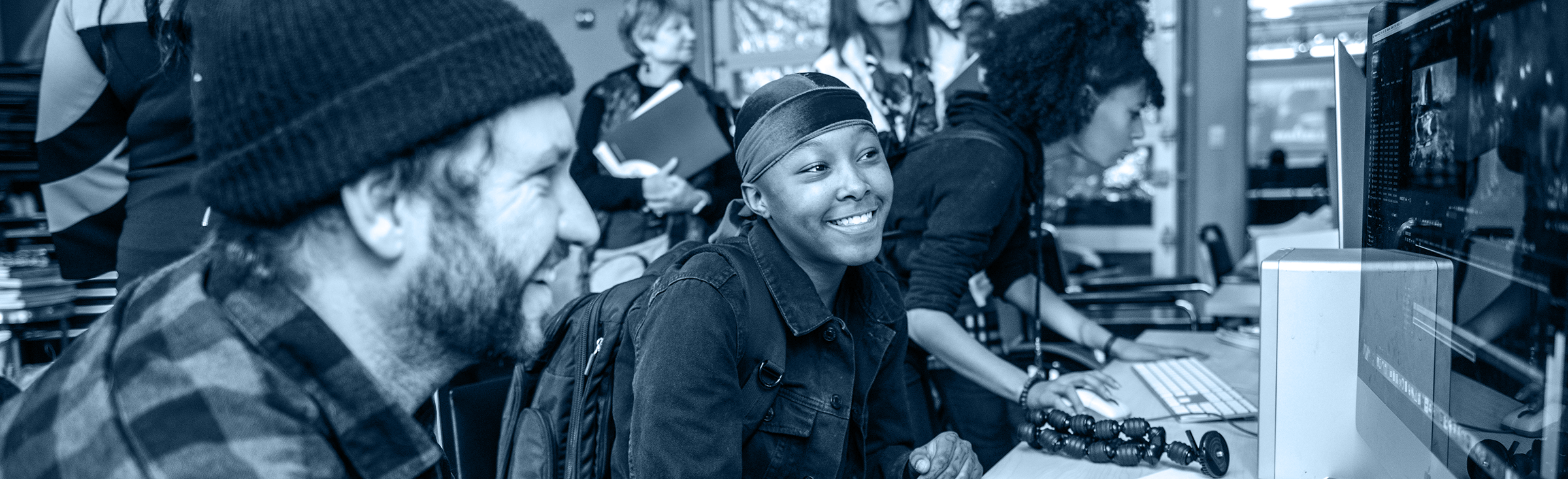

They say that there’s nothing more powerful than a good story. A protagonist with a clear and honorable motive. A setting that’s familiar, yet unique in its own way. And a plot that’s filled with joy, sadness, and even some laughter. In my experience as a teacher, I have always found it difficult to get students to tell their stories. The story behind “what you did this weekend” would always be “sleep” and behind “what you did over the summer” … was inevitably also “sleep.” However, you could always tell that within every student, there was a much deeper and more profound story to be told—a story of conflict and challenge. Of culture and family. Of journeys from worlds away and traditions rich in ethnic history. It’s why Allisón Chalco, a high school art teacher in downtown Los Angeles, doesn’t just ask students to share their stories, but rather, their Historia.

The distinction being that one’s Historia encompasses the stories that go far beyond just our own. Historia delves into our ancestry as well as how the stories of the people around us breathe into our own. Navigating through students’ Historia was the goal of Chalco’s curriculum unit this past Spring, and through a student-powered, creative and resilient lens, Chalco was able to design a series of lessons which allowed students to examine the narrative of immigrants while addressing Art standards like the color wheel and theory.

“As a teacher and at the heart of it, I wanted students to tell their Historia through culturally-sustaining storytelling. I wanted them to cultivate a critical consciousness and see art as a tool for social justice.”

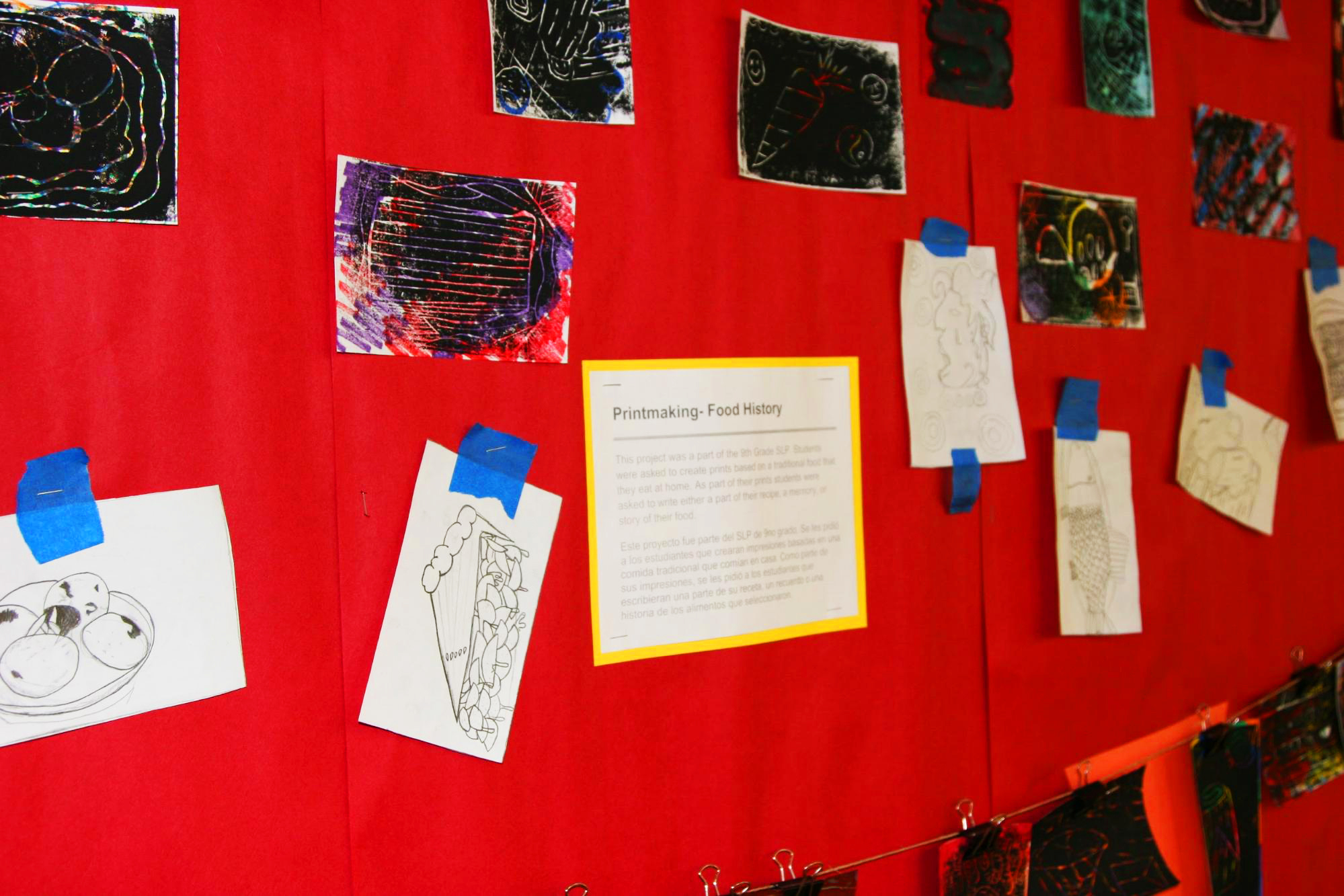

The School of Social Justice at Miguel Contreras, where Chalco teaches, is a standards based school, but, this still allows teachers like Chalco to exercise a level of curriculum autonomy where students can paint their learning with a full palette. Earlier this school year, Chalco encouraged students to bring in family recipes for students to be the subject of printmaking. She described the experience as one of the first times that she saw students truly open up to her as well as other peers in the class. The following semester, she created a much more comprehensive unit incorporating Historias throughout her curriculum.

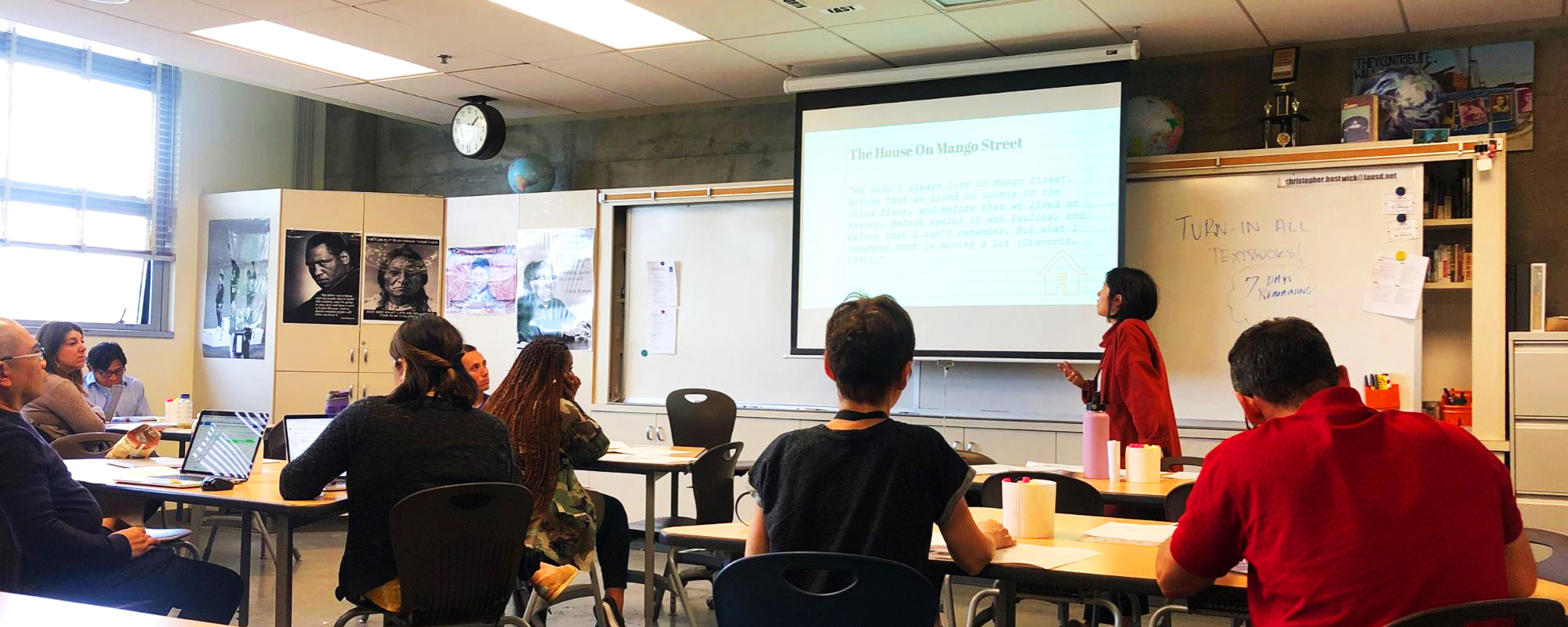

What began originally as a series of lessons on mixing color and exploring paint, soon transitioned into a unit that had students reading a book from their childhood, The House on Mango Street, while trying to address the driving question: How do Historias push through the White middle-class norms of language, literacy, and cultural ways of interacting? The House on Mango Street was written by Sandra Cisneros from the perspective of Esperanza Cordero, who struggles to find the expression of her Chicano culture during the late 20th century Chicago. From a selection of chapters in the book, Chalco tasked students to transform excerpts in the text that they found compelling and turn those excerpts into illustrations that helped capture the emotional weight of Esperanza’s experience. Chalco aimed to use the book as a tool for validating students’ experiences, but also as a “vignette to a larger classroom story” that she wanted students to explore: their own.

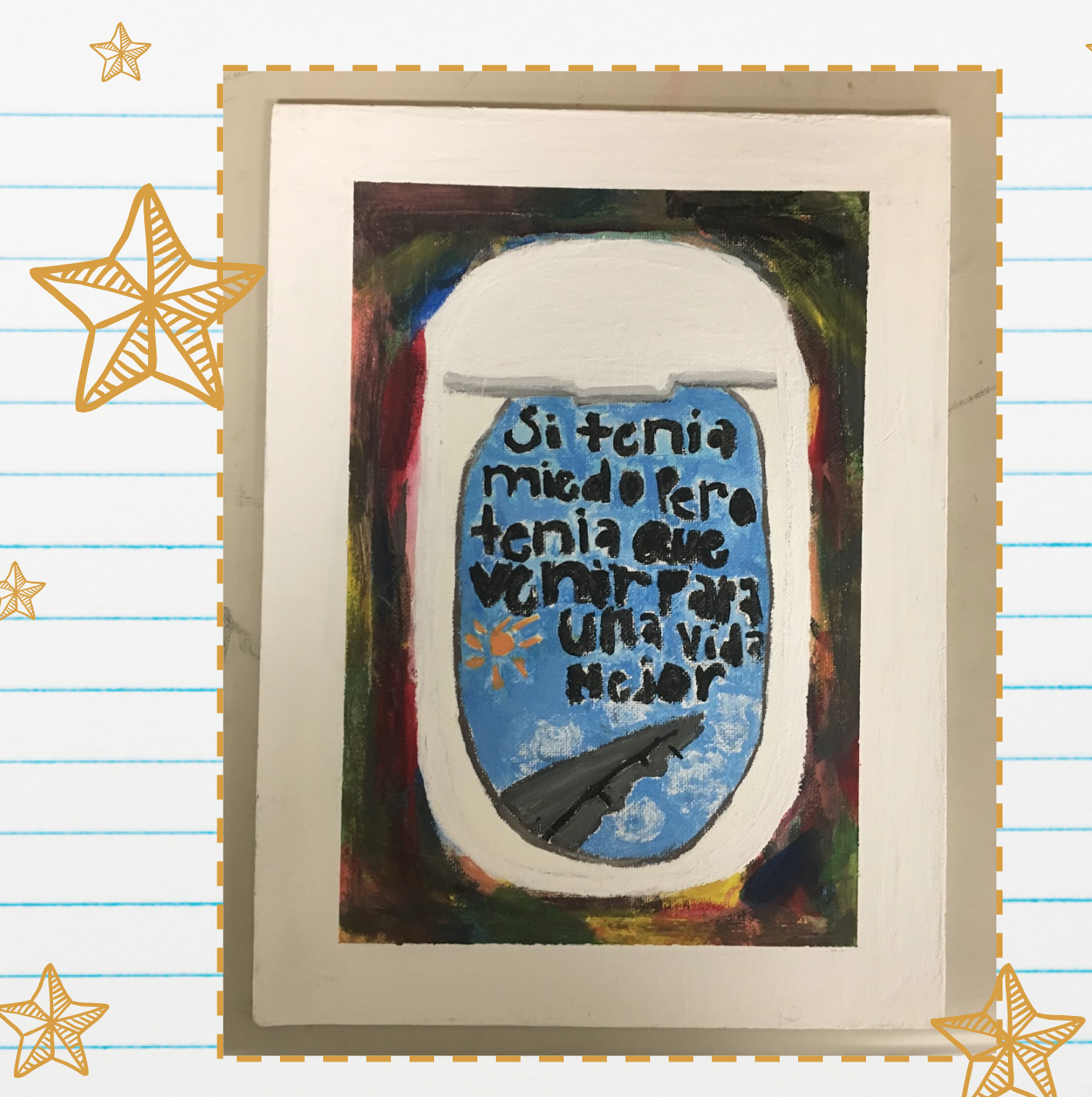

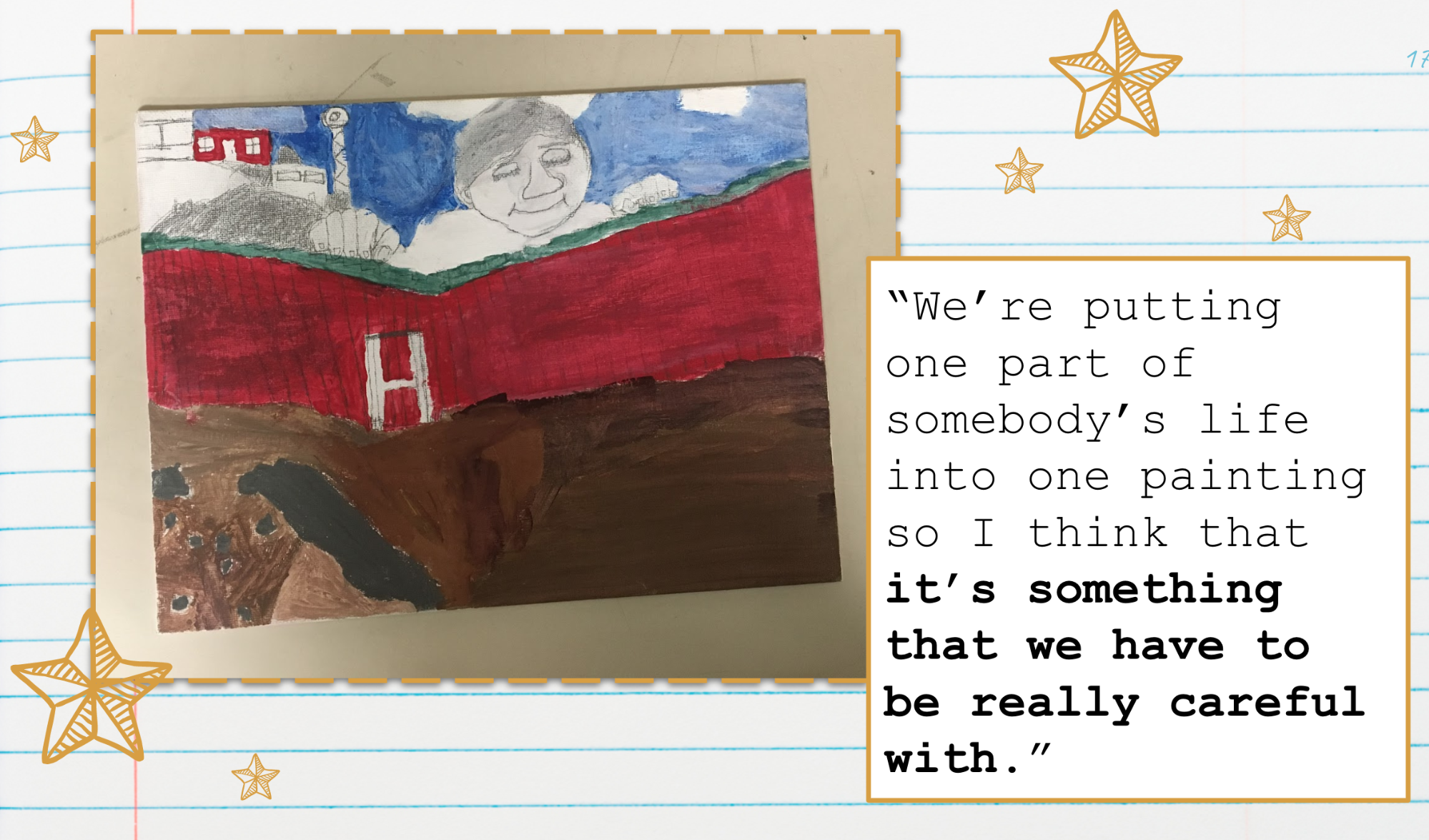

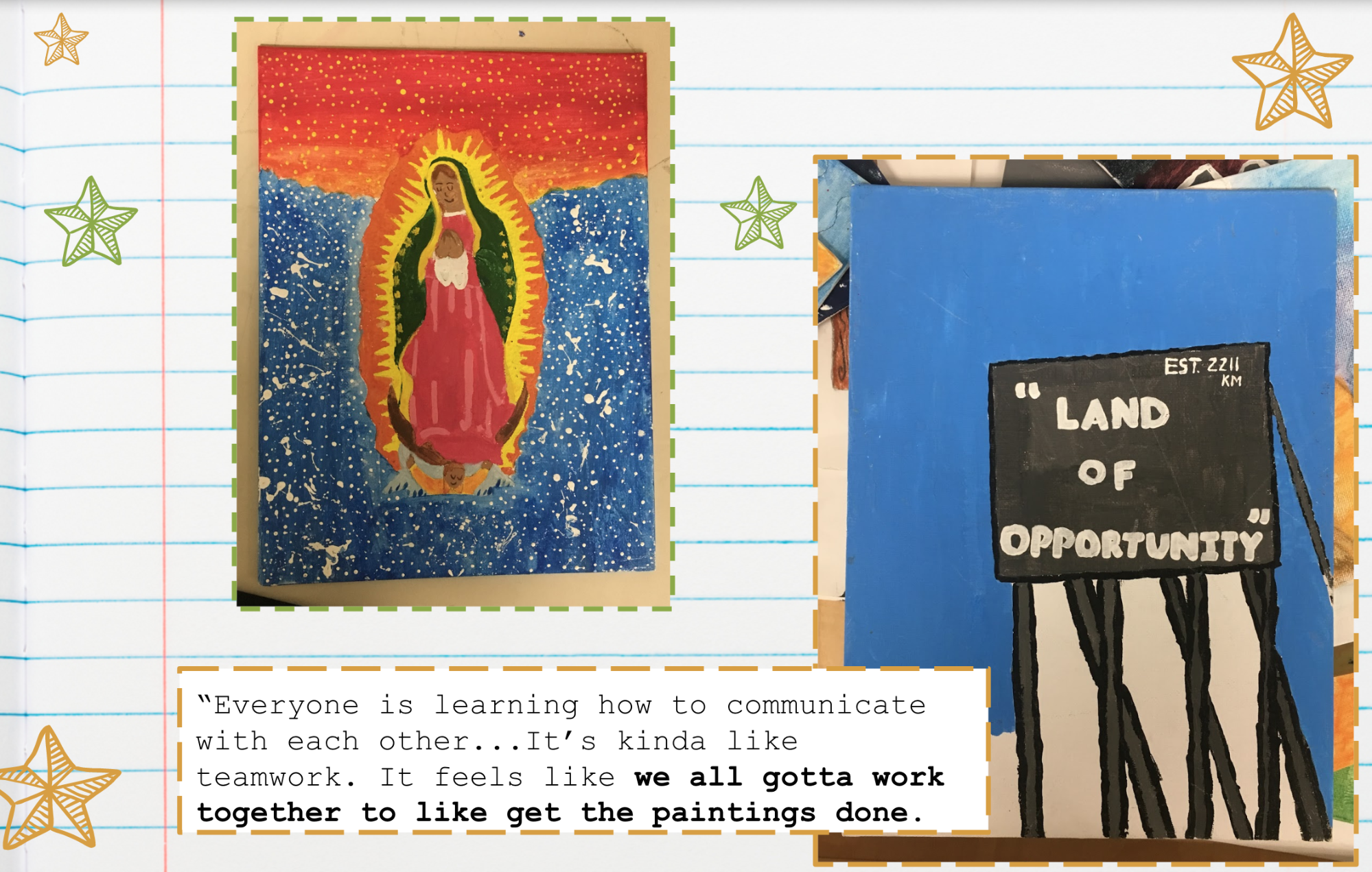

After students completed their House on Mango Street illustrations, Chalco’s next task was to have students transform their own stories into illustrations; but rather than having them look within, Chalco tasked them to look outward. She had them look at their teachers and their parents. At the people in their lives who shared a common thread with their own story, and at the fact that the narrative of immigrants is often lost and not seen as a collective story that we all share—an Historia. The illustrations that students would go on to create were paintings based on interviews conducted with folks who immigrated to the United States.

After students selected the subjects of their illustrations, they began to generate questions that would help them understand their subjects and develop their illustrations to the fullest. To model this process, Chalco performed an interview of her own—with her mother. As she shared her interview, Chalco explained that “every interview would look different” and that “the questions you might ask might be different from mine.”

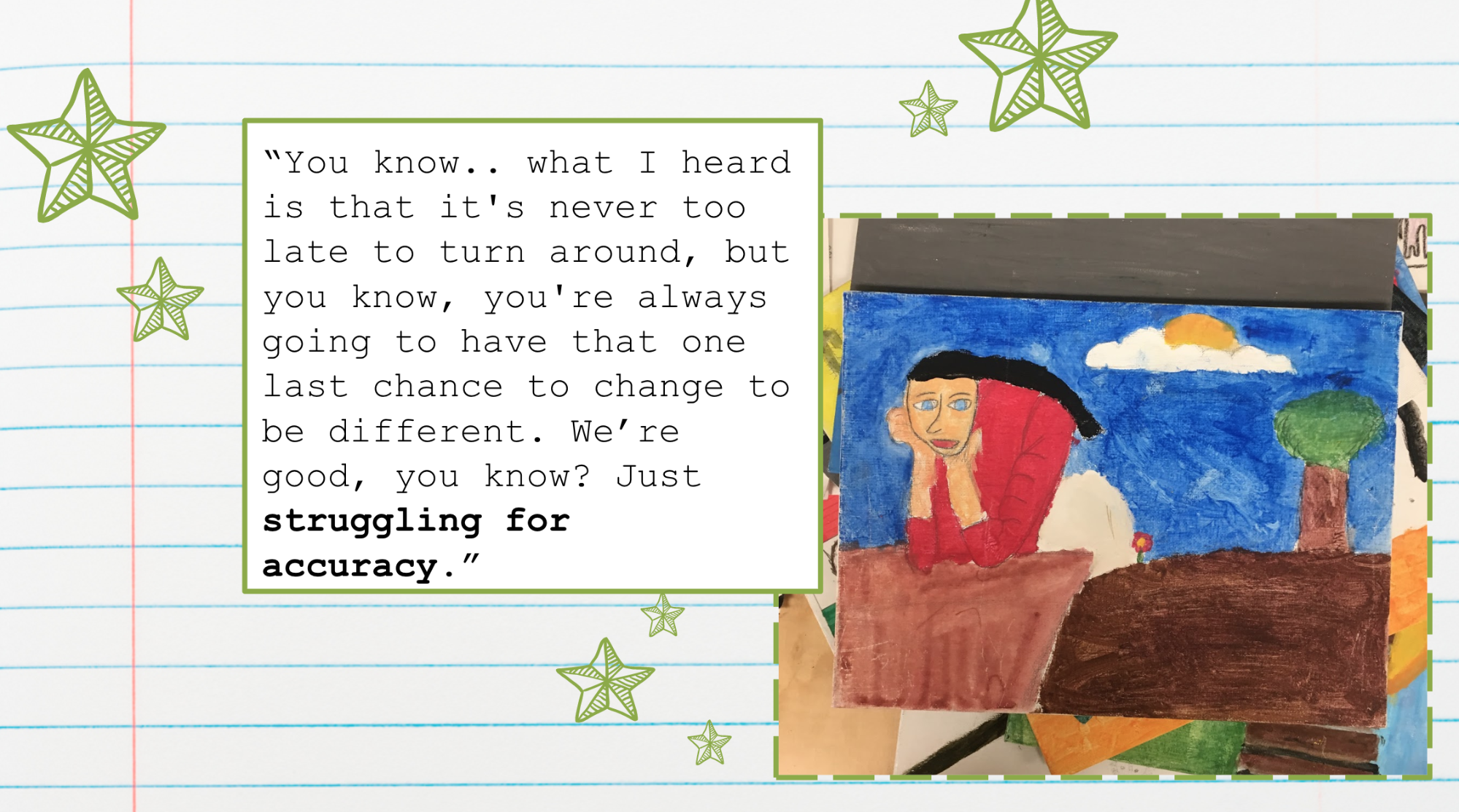

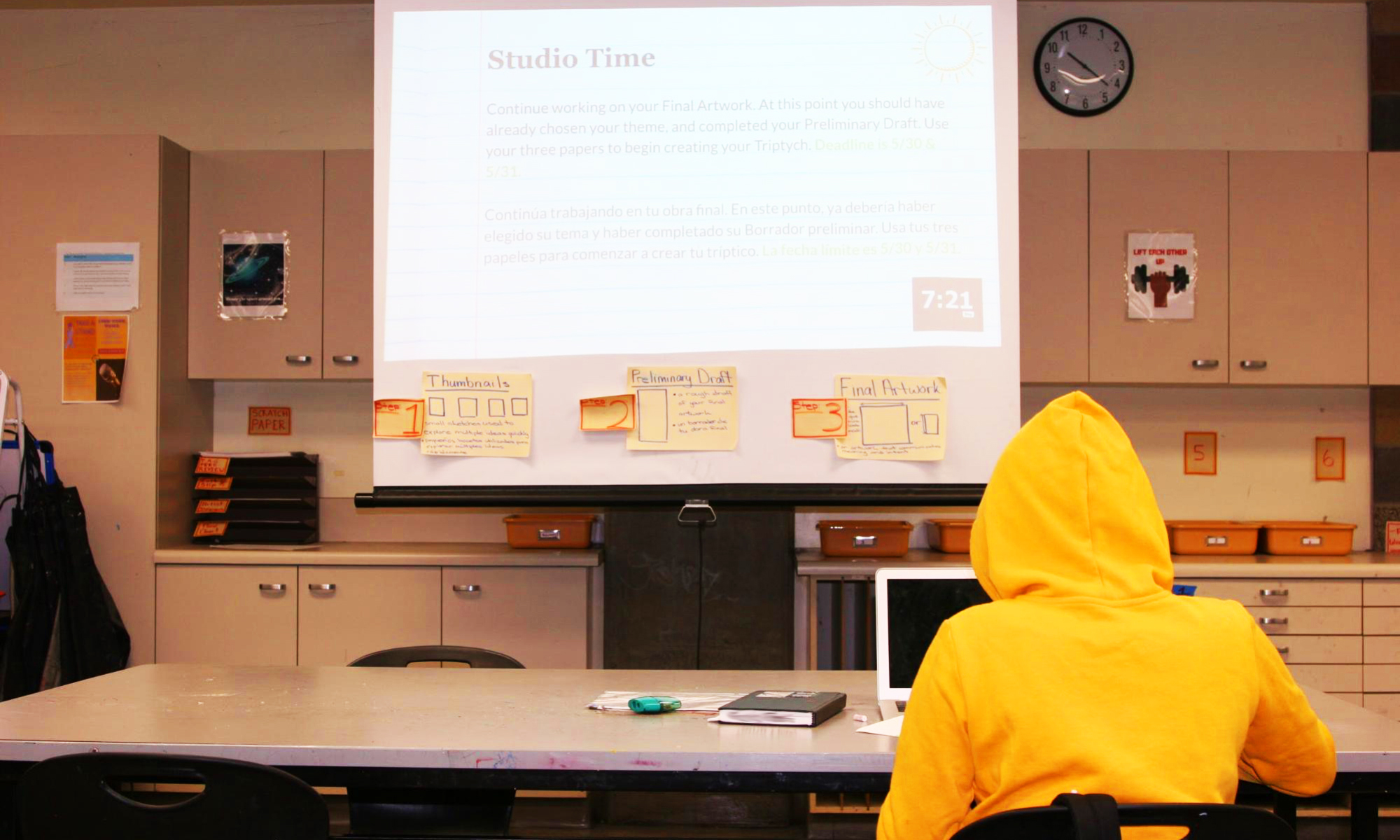

Collections of student work from student’s Historia interviews.

By applying the art practices they had researched and learned, the students were able to bring to life the stories of their subjects, all while discovering and connecting to their own Historia.

Upon examining the work, Chalco found that her students “demonstrated a sense of duty in telling their interviewee’s story, recognized the collaborative effort that took place while creating their paintings, provided a sense of achievement, valued the diverse experience of immigrants and their peers, and identified technical skills and steps for improvements.”

“For one of my students, he realized through the project that he wanted to spend more time with his dad. It’s been a very powerful project for my students and myself.”

Jonathan Tam is a science and math teacher at the School of Social Justice at Miguel Contreras. He is currently one of the core members in the LA Regional Network.

###

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP