Illustrations by Khou Vue for Education Evolving

Abruptly shifting to distance learning is a shock to the system for any student, but especially if you’re used to going to school among sharks and tide pools. Such was the case for students at West Hawaii Explorations Academy, or WHEA (pronounced “WAY-uh”) when Covid hit last year.

WHEA is a project-based, science-focused middle and high school on the Western shore of Hawaii, “the Big Island.” In a typical year, the island climate allows students to learn mostly outdoors. Their campus includes a lagoon pool and thriving aquaponics system. A nearby 3,000-foot deep sea pipe allows students to collect all manner of marine creatures.

As the first “start-up” charter high school to open in Hawaii, WHEA has earned national attention for its hands-on curriculum and student-led research projects. According to the school’s website, self-directed students who wish to challenge themselves thrive best at WHEA, but “a ‘can-do’ attitude almost always outshines innate ability.”

Finding a “WHEA Way”: Responding to Covid-19

Like at many schools, WHEA’s response to COVID-19 has evolved quarter by quarter since the start of the pandemic. With most of the school year already behind them, WHEA teachers collectively decided to finish out the last quarter of 2019-20 more or less as planned, but over Zoom—an impressive feat for a school almost entirely based on outdoor, hands-on learning.

Lead Middle School teacher, Kim Manuel, shared that her team worked “countless hours” to “bring WHEA to the students virtually.” Where possible, students continued working on their long-term research projects, leveraging webcams and shared documents to collaborate. “They did this amazing job,” Manuel said, but “it literally drained my team. They were spent. It took so much time, energy and effort to do what we took for granted being on campus.”

Come fall, the middle school team took a step back. Recognizing their present workload was unsustainable, and concerned that incoming 6th graders would struggle with project-based learning having never stepped foot on campus, they turned to an online learning platform to ensure students could access a state-approved curriculum while staff regrouped.

Meanwhile, in the high school, students were given three choices: a completely online, self-guided curriculum; an integrated approach that included both self-selected projects and the online curriculum; or a virtual version of “the normal way of doing things” for students hoping to come back to campus—a completely project-based curriculum.

As the year progressed, WHEA staff were able to incorporate more and more project-based learning into their students’ schedules. When Liana White, WHEA’s lead high school teacher, and her students could finally be back on campus, there was a collective sigh of relief. “Everything was just so much more doable then,” White said, attributing her teenage students’ renewed motivation to being together in a collaborative learning space.

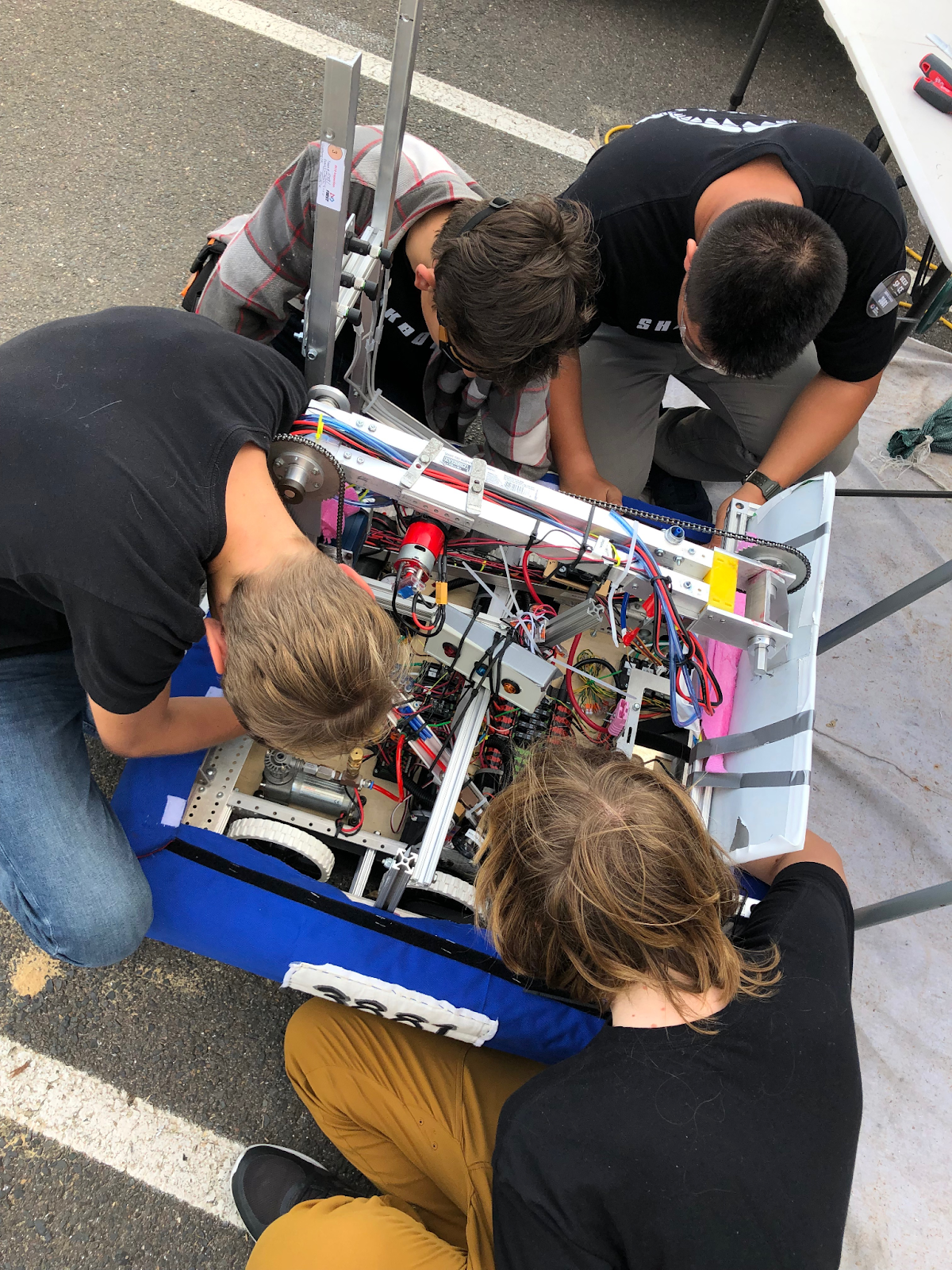

WHEA students collect samples on rocks on the Western shores of Hawaii

Principle 1 in Practice:

Student-driven scheduling means learning anytime, anywhere

One element that sets WHEA apart from most traditional secondary schools is its approach to scheduling. “We don’t have bells here,” Nakakura told us. “We don’t have someone going around blowing a horn, [saying] ‘Okay, period one is over!’ We have a fluid timeframe.”

Students use planners to manage their own time, deciding when they need to be where, and what they’ll be working on during that time. “A student’s schedule is a blank sheet of paper,” White said. “Each kid’s schedule is actually different because it all depends on what projects they’re involved in.”

Managing time is a skill that must be learned, which is why new students to WHEA and middle school students have more structured days. “We classify kids here as—instead of freshman classes, sophomore—it’s new and returning,” Nakakura said. “So new students here have a different schedule because they need more support.”

Pre-pandemic, the “WHEA way” had not only meant flexible, student-driven scheduling, but flexibility in terms of where learning took place. Even WHEA’s sprawling outdoor campus couldn’t contain its curious students, who wanted to do meaningful work in the community. Manuel described a middle school dolphin project where students designed a mobile learning experience for elementary students based on their research findings. At the high school level, students would normally serve as docents for “Aloha Kai Eco Education” tours, where they would share marine biology and engineering “mini-lessons” with up to 2,000 visitors a year.

With students learning from home this past year, off-campus and community-based experiences were not an option. But staff went above and beyond to bring hands-on experiences to students virtually. For a coral survey project, one high school teacher used a snorkel and a GoPro to capture video footage that students could use to collect data. Another teacher figured out how to bring a traditional kapa-pounding project home to students and facilitated a material-dyeing session with students over Zoom.

WHEA teachers also found ways for students to leverage their home environments as places of learning. One challenge organized by the middle school team was branded, “Help your Hale” (Hawaiian for house). “We had them go around their house and take a look and start to kilo or observe things in their environment that they felt needed tending to. What were the purposes of those spaces and places for the family? And then we had kids design and engineer ways of reconfiguring spaces so that it could be a place and space for family time, or [if] families were in need of something… the kids engineered an idea.”

Principle 1 in Evidence:

Holding students accountable for using their time wisely and making progress

There’s a stereotype that Hawaii residents live on “island time”: a relaxed, go-with-the-flow approach to going about one’s daily activities. But at WHEA, “students are held accountable for every minute of their day,” Manuel told us.

All students learn to use a Time Management System, or TMS, to plan out in advance what they hope to accomplish in every 15-minute stretch of the day. Teachers oversee and sign off on students’ progress toward their work goals, which earns them points toward their final grade.

WHEA founders developed the TMS as one way to assess students’ progress in a project-based school. “We had to figure out, how do you grade and hold kids accountable? And we started looking at, ‘How do they spend their time? How do you know they’re productive?’” Nakakura said of the system’s origins.

With stricter limits posed on students’ whereabouts and more structured schedules during the pandemic, the TMS has taken a back seat, with middle school teachers choosing not to use planners and high school students using them only to plan their work time within predetermined blocks. “We’ve been confined by logistics like no other year,” White told us. What impact these changes will have on students’ preparedness for self-directed learning next year remains to be seen.

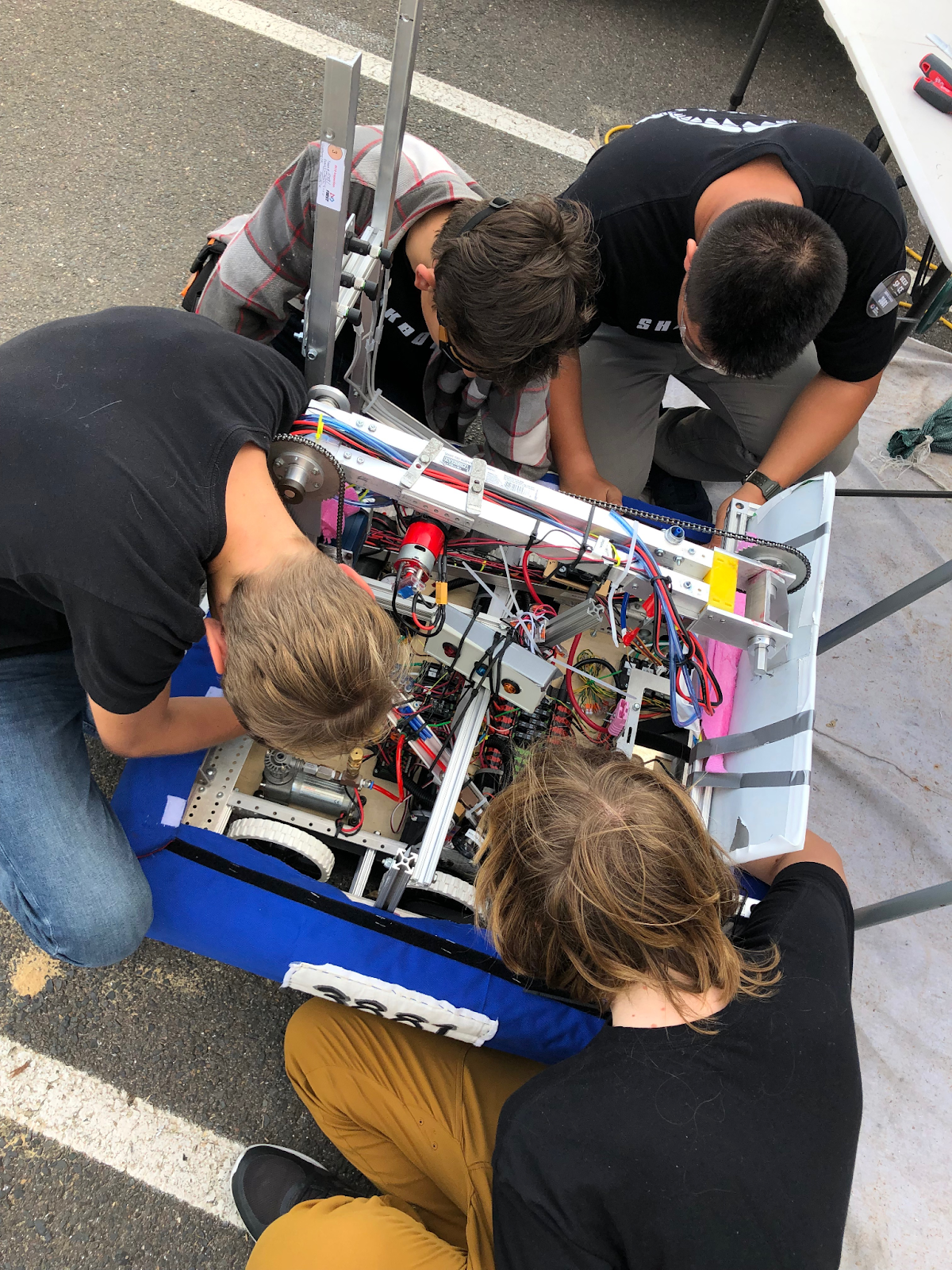

Teachers meet on the outdoor campus at WHEA

Principle 2 in Practice:

Student interests drive learning, expanding their ownership and agency

To students, learning to manage their own time means they get a lot of choice in how to use it. Students select projects that are interesting to them, which is why every student has a different schedule.

“It’s all about what the kids want to do. We’re along for the ride.”

“Students don’t go to language arts or science classes. What they do is they join projects,” Liana explained. Really interesting projects. WHEA is home to two black tip sharks that live in a lagoon pool on campus. “You can choose to be on sharks, that’s your choice,” Nakakura shared. Every year, high school students who choose to be “on sharks” work together to design an investigation. This year, students tested the effectiveness of different sound frequencies to deter sharks. By the end of the year, whatever the project, students will have completed an entire research paper following scientific journalistic conventions.

Adaptations have been made to projects due to COVID, but even those incorporate an element of choice since students have been able to choose how they learn this year. “There’ll be a group of students on Zoom, virtually looking at the sharks while those that have chosen to come back to school are actually working on the experiment,” Nakakura explained.

There were fewer projects offered this year than in typical years. Other high school projects included an investigation of the relationship between tide pool size and biodiversity, and a project to develop a sustainable food source for farm-raised tilapia. “Although it’s not the abundance of choices that we normally have during our normal school year, we still feel that getting that choice is important.”

It’s regular practice at WHEA to poll students to gauge their interest in various projects. When the seventh grade team was ready to incorporate more project-based learning come second quarter, they had students vote on the projects they were most excited about. Among the projects students chose were Native Hawaiian creatures, biomimicry, and other passion projects.

“We see our students as our clients,” Manuel said. “Without them, we don’t have the opportunity to engage in what we’re so passionate about. So we really take their ideas and perspectives to heart when making changes.”

For White, the student ownership piece is what has kept her at WHEA since 2004. “It’s all about what the kids want to do. We’re along for the ride. I’ve never thought of my job as pushing kids in these square-pegs-in-round-holes situations… What can we do that you want to do and I want to do too? Let’s make it happen.”

Principle 2 in Evidence:

Demonstrating evidence of learning from multidisciplinary, choice projects

With WHEA students having such varied schooling experiences based upon their interests, how do staff gauge their learning in any systematic way? They don’t do finals. They don’t test. Instead, students contribute to an evidence folder—a compilation of what they’ve learned and created over the course of the year.

At the end of each quarter, high school students present their evidence folders to their parents and teachers (virtually during Covid). Their presentations are scored according to a comprehensive rubric that incorporates elements from the research paper projects, a secondary project, and “Advisory” items (including the TMS). Presentations are opportunities for students to discuss what they’ve learned at a high level and to showcase what they’re most proud of.

The middle school team had to make adjustments to the way their students showcased their learning due to the pandemic. Instead of hosting family and friends for a “curriculum share fair” on campus, middle school students designed their own websites to share their learning processes and products with their ‘ohana (family).

Projects earn high school students credit across multiple subject areas. For example, writing a research paper—an expectation of all WHEA students—counts toward both science and language arts. It may incorporate social studies or math as well. “Our projects have been created to accept any content,” White told us. “There are specific pieces that students are required to show, but the content, specifically, it’ll take any direction.”

Likewise, “integrated course” grades are made up of various components, including the Evidence Folder presentation, research paper, and other projects. A Language Arts grade, for example, includes an oral communication component as well as written work resulting from project participation (see below).

Not everyone appreciates WHEA’s nontraditional approach to student assessment. As the Executive Director, Nakakura—who is retiring in December—worries about what’s next for WHEA for this reason. The State expects WHEA to make progress on standardized accountability measures—but a narrow focus on raising test scores just isn’t the “WHEA Way.”

The WHEA Way is to invest students in their education by giving them ownership and agency over what and how they learn. “When it comes to this age group,” White said, “if they’re not bought in, if they don’t feel like they have anything invested, if they don’t feel like they’re a part of the process, then it’ll just be hoop jumping for some. And for others, they just won’t do it.”

Conclusion

With significant input from their students, teachers found a way to “bring WHEA home.”

At a school where online schooling was a far cry from the immersive, hands-on, outdoor education students were used to, the transition to distance learning at WHEA was a particularly bumpy one.

A standards-based online learning platform provided immense relief and needed time for WHEA teachers to redesign project-based learning in a safe and engaging way. But “that is not us,” Nakakura said of the online curriculum. “There are schools that do online programs, but it is not WHEA. And so trying to be authentic and stay true to your vision and mission has been very difficult.”

And yet—with significant input from their students—teachers found a way to “bring WHEA home,” creatively adjusting group projects and reimagining the school day for a hybrid format. It took a lot of work, but staff were committed to meeting the needs of their active, inquisitive students.

Of the whole Covid experience, Nakakura says the easiest thing has been “working with the kids.” Among students who have chosen to come back to school, discipline problems have receded, and students are “just so appreciative”: “you just give them general reminders, ‘hey, put your mask all the way over your nose,’ or, ‘remember six-foot distancing.’ But they thank you. Like, ‘gosh, thank you for letting us come back.’ And they’re so positive and so that’s the best thing.”

White and Manuel were similarly appreciative of their WHEA team. “I really want to commend the staff for just sticking to what we know is right and dodging all these crazy fireballs thrown our way,” White said. Likewise, Manuel gives her middle school team and students “a big high five for being open to growing through this difficult time. Mahalo to the advisors for their patience, flexibility, creativity and ability to think outside the box. And to our students, mahalo for being you and sticking with it!”

Since everyone’s been back on campus, White sees the fruits of their labor: “Being able to see students working out in the garden, to see students going out to do data collection… doing these things that we know are the best parts of our school, I think it’s only possible because we took this kind of crazy hard path.”

About This Series

This blog post is part of a larger series exploring the practices and success indicators used for student-centered learning in a pandemic—and beyond. We are grateful to the Leon Lowenstein Foundation for their generous support for this series.

Read More & See Other Posts

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP