“How’s that working out for you?”

Any time I explain to anyone in traditional public schools how Avalon School — where I’ve worked since 2002 — has no principal, no director, that is the response.

“How’s that working out for you?”

It means in the middle of a pandemic trying to get a couple dozen staff to hammer out a plan where some students attend in person and others online. It can look messy, and I would be foolish and a liar to say we are always pleased with the result. However, the result is ours.

Teacher-powered schools can and do have principals or directors, but the philosophy is the same and may be obvious when looking at the language: teacher-powered. It means teachers are expected to read the CDC guidelines as we brainstorm our approach. It means teacher voices and questions must be part of the decision-making process.

Avalon has many new staff members this year, and it is not easy to convince them that this messy approach ultimately balances voices and vision. We are, after all, a predominantly white institution with experience and perspective that allow for vision as well as blindness.

One of the things I do at Avalon is co-coordinate the onboarding process for new staff. It means remembering telling them where to park but more importantly means talking through how we do our work at school. A new staff member has a plan for an afterschool program; what’s the process to take that idea from thought to action?

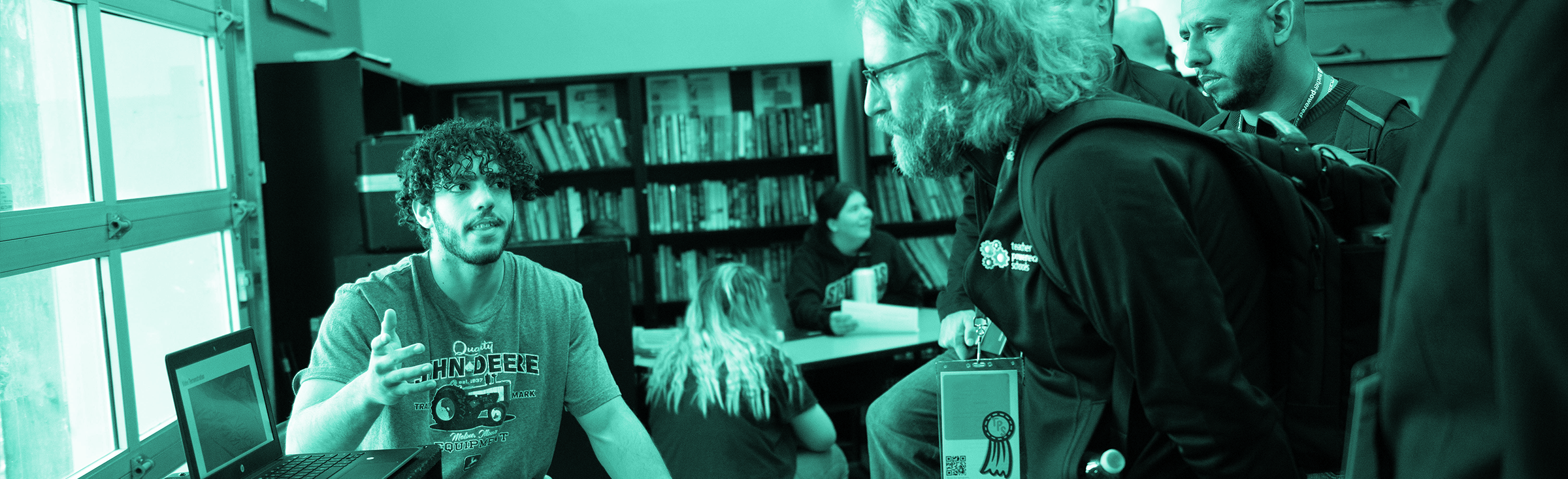

I could try to flowchart it out, but the flip answer is that it takes a good deal of talking. We have to check in with each other — sometimes on committees but most of the time informally, maybe at lunch or at meetings with a mentor. Many hands, many voices help move the idea forward. One person knows the logistics of cost, another helps to clarify the offerings, while a third recommends people and partnerships for support. There is no one person who gatekeeps nor one way to develop an idea. The collaborative process requires us to run our ideas by each other, get feedback, and continually improve our work.

One inevitable byproduct of teacher-powered decision-making is impatience, but we know that a sign of white supremacy is a sense of urgency (Jones and Okun, 2001). Conversations take time. They can slow us down but (I hope) not discourage us. The goal is to make the plan workable, whether we are discussing learning options in a pandemic or an afterschool program.

The true challenge before us is to encourage and inspire the newest hires along with the most seasoned veterans that we must find a way for all of us to engage with the decision-making process. Sometimes this means delegating with trust; other times it means making time for reflection. Or, at a recent meeting, it means meditating as a group before we address the existential purpose of our professional development: how do we get better at what we do?

Have our trainings helped us to get better? A teacher-powered school asks questions like that, so, in the end, we experience our work not as something done to us or done to students but done together, hammering away at plans and procedures and protocols that call each of us in, in our own way, to contribute to the running of the school.

How is it working out for us? After more than twenty years, I can say that the mess, if we can make it and unmake it together, is worth it.

###

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP