The beginning of the teacher-powered movement in Minnesota came with the passing of the nation’s first charter law in 1991. With teachers taking on the roles of founders, board members, and administrators—as well as teachers—the shift began. At that point, teachers had the power to control the school environment. With the seventh charter school in the state, the Minnesota New Country School in 1994, another radical idea found a home: the idea of teachers as owners of their intellectual capital. Along with the innovative practice of personalization and project-based learning, the founders also created EdVisions Cooperative, in which teachers organized in a professional practice that contracted their services to school boards and provided services to members.

This development espoused the idea of teachers as owners, not employees. This has elements of entrepreneurship and the “business model.” Teachers were contractually responsible for services, had control over accountability for results, determined their own fees by controlling budgets, and were able to determine membership via peer review. The business model of “for-profit” education did not go over well, especially in Minnesota. But the concept of a democratically run cooperative was acceptable to the public, and so the cooperative still exists, with 14 schools in membership, and over 250 teachers as members. Also, it fostered a number of other teacher cooperative groups in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and a few other states.

The concept of teachers as owners rather than employees has meaning in Minnesota. This concept, first appearing in 2002 in the book Teachers as Owners, is not easily discovered within the teacher-powered movement elsewhere at this time. Teachers, for the most part, still see themselves as employees of school boards, even if they have the power to make the most important decisions. But this idea appears to be the only of the early ideas to not have legs.

Teachers as Owners also made the point that with teachers in power, schools ought to create a culture where the members exhibit caring, creativity, good communication, self-reflection, celebration, and a strong sense of purpose. It appears, from what I learned at Teacher-Powered Day in Minnesota on November 9, these concepts have definitely prospered.

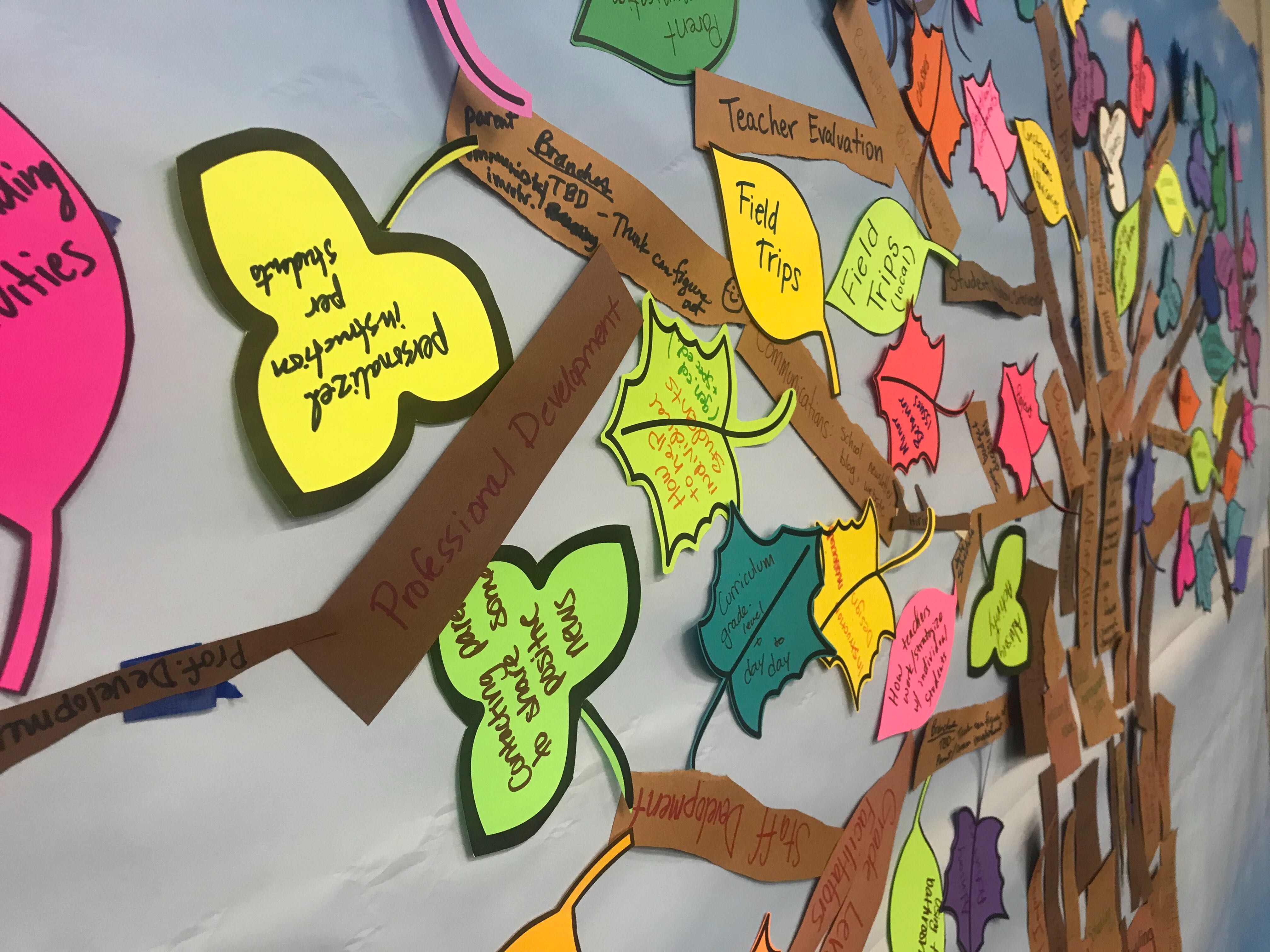

From the books Democratic Learning and Leading and Teachers as Owners came ideals of a successful professional practice, and would be the practices hoped for in the future:

- Power would rest with the teachers, who would share decision-making with parents and children;

- Work is shared through shared knowledge and time;

- Control rests extensively on systems designed to meet the needs of children (i.e., personalization);

- Functional units in organizations support professional needs of teachers;

- Leaders are successful only as they serve the needs of teachers and children in shared leadership roles;

- Selection of members is most important to the success of the organization;

- There would be a commitment to accountability for results, and continuous improvement mechanisms would be in place.

In the Education Evolving publication called Teacher Powered Practices, a number of these practices are outlined that exhibit the above ideals. We learn of schools from across the country that are placing student needs first and at the center, and schools that are practicing what was hoped for early in the teacher-powered movement:

- Students are at the center of decision-making;

- Parents and community are meaningfully involved in the schools;

- Student voice and choice are honored;

- Collaborative cultures are cultivated;

- Transparent decision-making is evident;

- Shared leadership structures are in place;

- Peer observation takes place; and,

- All participants take upon themselves a learner’s mindset.

As these practices evolve, we see the past become the present, and envision an even more promising future. From presentations by Dr. Richard Ingersoll and Doctoral Candidate Sarah Kemper, we learned that research is supporting teacher empowerment with such practices mentioned above. Ingersoll found that schools with “higher levels of instructional leadership and teacher leadership rank higher in student achievement, for both math and ELA.” Furthermore, the study showed that “those elements of instructional leadership and teacher leadership that are most strongly related to student achievement are least often implemented in [traditional] schools.” For example, those schools where teachers have “large roles in student discipline procedures and school improvement planning are more strongly related to student achievement.” This study is strong evidence for teacher empowerment.

Ms. Kemper found that teacher-powered schools, exhibiting some of the practices above, were ranked higher in almost all measures used in her research. Her research found that teacher and student voice, the expression of ideas, more inclusiveness, and transparency in decision-making were more evident in teacher-powered schools. Also, teacher-powered schools appear to positively influence student agency via more personalization. Students exhibited positive relationships, understanding, and caring—all which led to more student agency. Students in teacher-powered schools appeared to be more engaged.

Obviously more research needs to follow the movement. But from indications thus far, teacher empowerment leads to student empowerment. What we were seeing as hopeful for the future 25 years ago appears to be present.

Two areas of concern, to those of us who were early in the movement, were development of pre-service teachers in higher education institutions, and the involvement of school districts in fostering the movement. As for pre-service institutions, Dr. Ingersoll assured us that there are a number of movements across the country where teachers are being taught leadership skills and how to develop personalized programs where student agency can be developed. Many district schools, which perhaps were hostile to the concept years ago, are now looking at creating more teacher-powered schools for two other important reasons: retention of good teachers, and job satisfaction.

As more and more practices are developed where teachers have the power to create programs that enhance student personalization and agency, we see the vision of those pioneers of 25 years ago has become more and more a reality. We are greatly encouraged. Kudos to Education Evolving and all those who work toward building a better future for teachers and students.

###

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP