This is the second of a two-part set of articles on Teacher Evaluation. See the first entry here. Contact Greg Fisher at schoolempowerment@gmail.com.

Is there more than one way to design and run a Teacher Evaluation program?

Of course there is. But why does the vast majority of schools’ deploy anachronistic and obsolete systems that are devoid of positive outcomes and don’t lead to significant improvement in instruction and student achievement? The reason is obvious. It’s because they don’t possess a teacher-powered mindset.

So, what gets in the way of having a teacher-powered mindset?

Let’s start with how the instructional and operational dimensions of all schools within K-12 education are always impacted by its socio-political context. Decisions about education are never politically neutral. They are tied to the social, political, and economic structures that frame and define our culture. There are laws, regulation, policies, practices, traditions and ideologies that are unique to every part of the nation.

A common by-product of this socio-political context is the vast preponderance of schools having a top-down governance structure. This leads to myopic thinking, preventing those with authority to relinquish their power and view those closest to students’ learning experience, school-site administrators and teachers, as having the greatest insight and capability to prescribe and implement an effective learning environment.

Doesn’t it seem counterintuitive that those farthest removed from school sites have the most amount of decision-making power? Instead of obediently following a bureaucratic and de-personalized system with it’s countless compliance edicts all emanating from district headquarters, decentralizing that authority (assuming it has earned its granted autonomy), would place more responsibility in the hands of school site faculty and administrators in the running of their school where they can have a more individualized and humanizing learning community (all operating within State Ed. Code).

To complicate matters, the trends in Teacher Evaluation are disjointed and unrealistic. They include the following:

- Policy is way ahead of the research in teacher evaluation measures and models.

- Though we don’t yet know which model to replicate and the combination of metrics that will identify effective teachers, many states and districts are pressured to move forward at an accelerating pace.

- Inclusion of student achievement growth data represents a huge “culture shift” in evaluation.

- Communication and teacher/administrator participation and support are crucial to manage the change. Because of their design and implementation, teacher evaluation systems have failed in affecting any significant progress on all academic data measurements.

- The implementation challenges are enormous.

- Few models exist for states and districts to adopt or adapt to.

- Many districts have limited capacity to implement comprehensive systems, and states have limited resources to help them. Hence, they continue to implement teacher evaluation programs in a limited, one-size-fits-all and ineffectual manner.

Finally, let’s look at what all schools have in common are it’s core functions. They normally include curriculum and assessment, attendance, budget, calendar, governance, staffing, and teacher evaluation. When it comes to student achievement, the most important goal for any school, which one of them do you think has the greatest potential impact? I would argue it is teacher evaluation.

Why? Simply due to the fact that teachers, the greatest resource of any school, have a direct and ongoing relationship with students in the teaching of content and skills and therefore have the largest impact on student learning. Teacher evaluation systems can, if designed correctly with the proper structures and processes that are grounded in teacher support and empowerment, can yield the greatest benefit to student achievement.

But here’s the problem. Whether you are a new or veteran teacher, a site administrator, or district and union representative engaged in collective bargaining, there is an acknowledgement that what is sorely in need of reform is the area of teacher evaluation. It is not considered meaningful, is dreaded as a perfunctory, time-consuming nuisance, and rarely results in weeding out or even supporting low-performing teachers.

In over three decades in education, I have yet to meet one person, administrator or teacher, who wholeheartedly and sincerely believes that the teacher evaluation system they have ever been a part of was valued or perceived it as being as good as it gets.

If we are to reimagine teacher evaluation and think about how to reform it to make it more meaningful and used as a process to promote improved teaching and learning, let’s rename it Teacher Collaboration and Growth Program.

Yes, teachers need to be held accountable. But we let’s place the emphasis on teacher improvement and figure out other means by which to maintain high standards of quality teaching. We do this with the knowledge and countless examples that educators who work in isolation improve incrementally, while educators who collaborate transform exponentially.

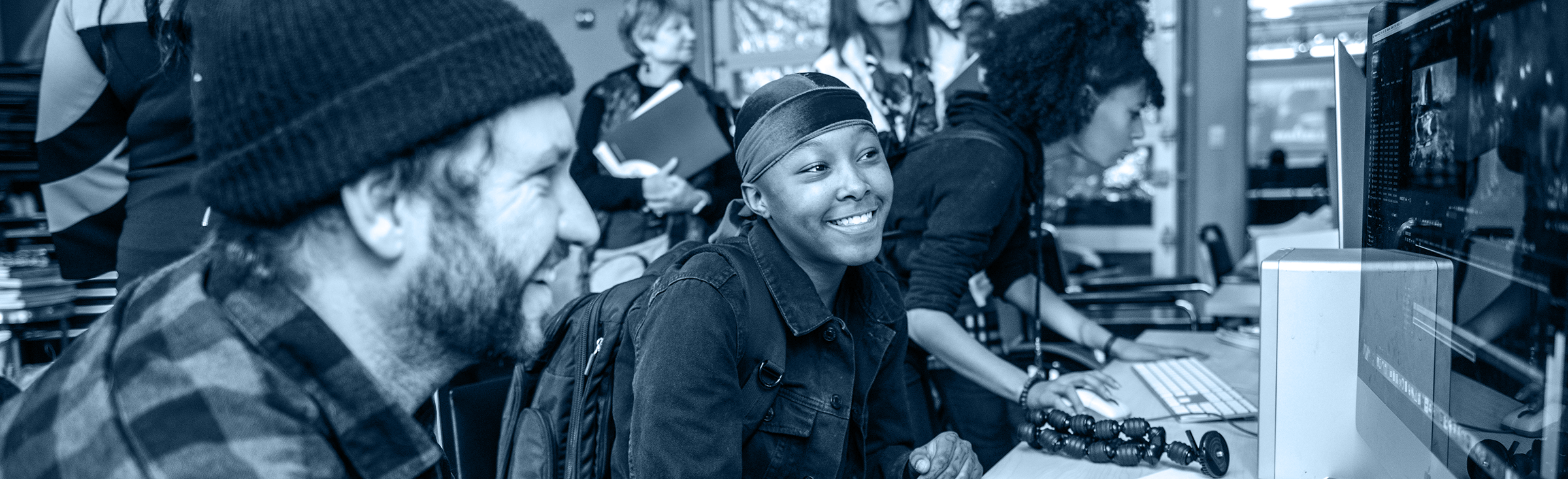

All schools’ collaborate in varying degrees. When working with schools, I like to post a collaboration visual and ask them where they think they are currently at in terms of collaboration and, secondarily, where they aspire to be. Invariably the responses for where they think they are now are all over the place. It’s always noteworthy that their perceptions are not aligned with one another.

But when asked where they aspire to be on the continuum, it is always to have more interaction and be on the far right of the diagram with the highest form of collaboration possible. I interpret this to mean that teachers are yearning to be less isolated and want more collegial engagement. So, the question becomes what is blocking the realization of a more collaborative school environment and how can they get there?

A school’s ecology requires strong connections. But traditionally, our nations’ schools have placed teachers to spend the vast majority of each day alone with students. When they do interact with their colleagues it is rarely to collaborate for the purpose of improving and supporting each others instruction or share best practices that benefit student outcomes, or provide effective feedback on classroom observations. Usually they meet in mandated faculty meetings or talk superficially in department or grade level meetings about non-academic content.

In addition, because educators are not trained in how to have professional, high-quality conversations, it is not uncommon for personality conflicts and toxic relationships to interfere with their conversations. If you think about it, all schools sort of just throw people together with various roles and job descriptions, and assume they know how to talk with one another. Teacher credential programs do not have courses/programs that help them learn how to communicate in healthy ways that are required when working in such intimate and demanding environments.

It is only through a cohesive and strong collaboration process can school staff thrive and feel connected. This connection will, over time, in the sharing of best practices in professional developments and departments/grade level teams, providing effective feedback through peer observations and collaborating on a wide range of discussions related to teaching and learning, lead to greater teacher effectiveness.

But what do we mean when we say we want all teachers to be “effective?” Teacher effectiveness defined, according to Goe, Bell, and Little contain the following:

- Have high expectations for all students and help students learn, as measured by value-added or alternative measures.

- Contribute to positive academic, attitudinal, and social outcomes for students, such as regular attendance, on-time promotion to the next grade, on-time graduation, self-efficacy, and cooperative behavior.

- Use diverse resources to plan and structure engaging learning opportunities; monitor student progress formatively, adapting instruction as needed; and evaluate learning using multiple sources of evidence.

- Contribute to the development of classrooms and schools that value diversity and civic-mindedness.

- Collaborate with other teachers, administrators, parents, and education professionals to ensure student success, particularly the success of students with special needs and those at high risk for failure.

If all or some of these are teacher effectiveness criteria you want to see within your teaching staff, then the question is how to use one’s teacher evaluation system to help manifest and monitor them? Let’s start with imagining a teacher-powered system that touches on the following core beliefs and approaches:

- Foster and promote a teacher-powered culture of reflection and professional development, leverage student feedback to help teachers grow, and alleviate the considerable burden the evaluation system placed on department heads and the administrators.

- Design a system centered on professional growth rather than for integrating new faculty or for disciplining underperforming teachers. Taking part in a professional growth system that encourages observation, feedback (from both teachers and students), and conversation normalizes a growth mindset, which is an integral part of any evaluation process.

- Celebrate faculty professional growth. Encourage faculty to engage in informal conversations on teaching and learning through weekly or ongoing opportunities to observe and share with colleagues what one is currently doing in the classroom; Department and Grade Level Team meetings that have agenda items on the content and pedagogy teachers utilize, contributions they make to the school, professional development that each teacher is pursuing, student surveys results, and multiple measures of student academic data. Allow faculty to share and make visible their learning and best practices with colleagues.

- Assure faculty that they have a voice and choice. Faculty feel a greater sense of ownership and therefore are more invested in their growth when they are able to choose their path based on their individual goals. All teachers being reviewed direct the flow of all conversations.

- Normalize non-evaluative observation and feedback. To build a mindset that allows the evaluation year to be more growth-focused and less anxiety-provoking, faculty-led professional learning communities are centered on observation, pre- and post-observation discussions, and decreasing the vulnerability that faculty often feel when entering an evaluative year. The goal is that over time all teachers genuinely welcome colleagues and guests to witness what goes on in their classroom.

- Respect the process. An administration that demonstrates respect for the growth process and the product of that growth is a key factor in the development and implementation of an effective system. Administrators must delegate their work and build capacity to ensure that there is adequate time and space for every teacher to pursue a professional learning path.

Teachers say they want more control in decisions regarding programs, curriculum, methods, and books. Then why is a review of professional practices someone else’s job?

Most traditional teacher evaluation systems focus on a formal observation process. The word “formal” elicits pressure, is consequential, and infers a high stakes event. With traditional teacher evaluation systems, hammered out between teacher unions and district officials, usually teachers wind up feeling pressured to perform for an administrator who makes one or two brief classroom observations and witnesses a limited snapshot of the teacher’s ability to teach effectively. The focus is on grading the teacher using a checklist of teacher evaluation focus elements. Not a lot of important feedback to reflect and improve on.

Instead, imagine a Teacher Collaboration & Growth Program that has a more relaxed, non-threatening and non-judgmental effect. The teacher being “evaluated” is in charge as all facets of the program. The process starts with the teacher making a reflection on essential teaching and learning focus areas (content, pedagogy, school contributions, professional development, and student surveys & data). That reflection then becomes the basis for conversations within Department and Grade Level Teams as teachers cultivate trust and solidify professional relationships with each other.

One idea triggers another, leading to the sharing of a variety of professional learning experiences. Then the teacher under review selects a teacher colleague from their Department and Grade Level Team and invites them into their classroom to make Peer Observations while teaching a lesson, with a pre-observation to discuss what to look for and a post-observation to provide effective feedback with supportive pedagogical ideas.

The process culminates with a Committee Meeting where all who participated in the process share their input while summarizing and highlighting key aspects of what the teacher experienced. In such meetings usually the teacher is celebrated and honored for their effort on a range of topics as well as identifying areas of improvement and mastery.

With the Teacher Collaboration & Growth Program, the real benefit of this process is it is school wide as all faculty members participate in it one way or another. Administrators are able to delegate teachers or out-of-classroom credentialed staff members to facilitate the program.

This form of distributive leadership empowers teachers as they become Co-Chairs, overseeing the entire program, gathering evidence, and providing input to administrators by providing updates and on the status of the program. It is best if the Co-Chairs are selected by the teaching staff. When schools commit to giving teachers more opportunities to collaborate and the freedom to choose how they want to support themselves with the goal of being better at the art of teaching, then the culture shifts, giving the term “Teacher-Powered” real meaning.

Our schools are only as good as the conversations within them. To guide teachers in this collaboration process, a series of professional developments are needed to help with cultivating communication skills (listening, questioning, empathy, dialogue), understanding transition and organizational change, setting up group norms, writing vision/mission statement, and consistently updating the progress made with check-ins and surveys are essential for the success of the program. Such a program takes place throughout the school year and because it is structured to be school wide in its participation, the time it takes to complete is very manageable.

Success, especially in shifting a school’s culture, doesn’t come overnight. It takes time for new ways of doing things to pay dividends. But once new beliefs and habits kick in, the process becomes institutionalized and a new normal replaces the old system.

Administering a School Readiness Survey is always an excellent way to gauge where the staff are at before full implementation. Initially, there will always be a few on staff that are gung-ho that will support such a change immediately. In the middle are the majority of fence sitters who will reserve judgement but will go along and test the waters. Then there are those few left who are resistant to change and will be trying to sabotage things because that is how they react to anything new. But over time, the entire faculty will embrace the program.

As a high school teacher and Principal, I witnessed teachers less isolated and more engaged with one another as our student achievement data improved after implementation of our Teacher Collaboration and Growth Program.

The benefits of such a program that turns the traditional teacher evaluation system on its head with the teacher under review directing the entire process are vast. These can include the following:

- A high-quality professional development tool that makes teacher evaluations meaningful and low-stress.

- Faculty self-reflection on their craft strives for greater transparency.

- More meaningful feedback that leads to improvement and empowers teachers in their own growth and development.

- Holds teachers accountable to one another, so teachers are motivated to change and improve.

- Enhances collegiality and professionalism among faculty.

- Provides assistance to new and veteran teachers to improve their instruction.

- Transforms teachers’ and administrators’ roles and relationships from adversaries to allies in improving teaching standards.

- Combats the climate of isolation that exists in many schools.

- Teachers develop skills in building strategies and lesson planning within and across disciplines and grade levels.

- Cultivates a flat, horizontal, egalitarian, and consensus driven school. Shifts the school’s culture. Elevates role of teachers as effective consultants and reviewers of fellow teachers.

- Outcomes of trust, honesty, being a team player, confidence, and interpersonal skills are all enhanced among the school’s staff.

- Transforming a school’s teacher evaluation program has benefits that permeate throughout the entire school as collaboration enhances teacher morale, decreases teacher burnout, and improves student achievement on a wide range of critical academic and social-emotional metrics.

The real lasting benefits from undergoing through this transformative process is when the school’s culture shifts, conversations become more transparent and relevant, and everyone begins to sense that there is more trust and stronger connections between people. All stakeholders begin to view themselves in a way that is closely aligned with Sheldon Berman’s take on the term community, “A group of people who acknowledge their interconnectedness, have a sense of their common purpose, respect their differences, share in group decision making as well as in responsibility for the actions of the group, and support each other’s growth.”

A meaningful, collaboration-based alternative to teacher evaluation is an exciting way to energize a staff, help even the best teachers improve their practice, and engage students with more a more dynamic learning environment. The bottom line: A single teacher can contribute to a net-zero world, but when an entire faculty comes together, collaboration has the power to effect deeper and more meaningful change.

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP