This blog post was orginally posted as part of a blogging roundtable in collaboration with the Center for Teaching Quality.

I remember sitting alongside Ayla Gavins, the principal of Mission Hill K-8 School, a teacher-powered school where I was working as a student teacher. A month in and I was feeling comfortable with my students, with my cooperating teacher, and at the meetings I’d been encouraged to attend. As we discussed a group of students’ behavior at our student support meeting, I put forward an idea to which Ayla responded by saying “I don’t agree with that at all.” I was struck dumb for the rest of the meeting. As we left, I was kicking myself for not listening quietly and knowing my place as a new student teacher — but I also know I’m not a person who can keep quiet when I feel passionately about an issue.

A feature of the school, not a bug

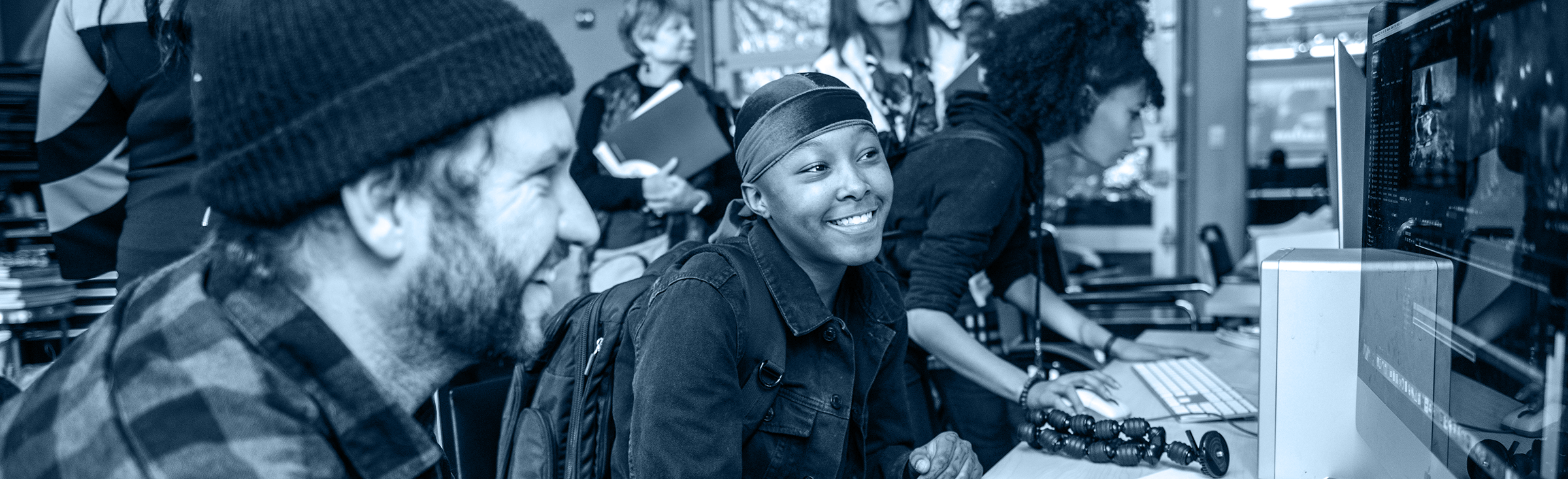

As it turns out, my need to voice my opinion was not viewed as a flaw by the staff, but as a strength. Mission Hill has over the years used their autonomy as a Boston pilot school to assemble a staff of tenacious, passionate, well-spoken teachers. Those who are quite comfortable arguing for hours on end if they are not satisfied with the direction in which we are heading. As one of my colleagues recently said in a meeting, “This staff did not come together by accident.” We are committed to running our school democratically. We recognize that respectful and extensive debate is essential to our work as a democratic institution.

At times this form of discussion can feel exhausting. Do we really have to talk for 90 minutes about whether students should be able to wear hats inside the school building? Does it really matter if we use similar language about self-regulation across the school? Is this issue really worth the argument? I often thought this way earlier in my time at Mission Hill. However, we have found as a staff that these disagreements are often the indicator of a deeper issue which needs to be discussed.

Looking out for our personal blindspots

Last year, we were discussing the daily schedule of the school. Geralyn (a teacher of our youngest students) insisted that students not arrive at their classrooms until the official start of the school day at 9:15, instead of 9:10 as had been happening the previous year. At first I was exasperated that we were spending so much time talking about a five minute time difference. But as the back-and-forth continued I could see how much Geralyn cared about this topic. At one point she said “I know it doesn’t sound like a big deal—it’s five minutes—but when you have a class of three year-olds it really makes a difference.”

Because we dug deep into this issue, I had the opportunity to put myself in Geralyn’s shoes; if my first and second graders arrive early, they get started on their work independently while I continue to prepare for the day. If Geralyn’s students arrive early, she has to help them take their coats off, get breakfast, and get settled in an activity. Her prep time is over. This conversation not only helped Geralyn get the prep time she needed, it helped the whole staff recognize a blindspot we had.

A work (ever) in progress

These disagreements happen all of the time at Mission Hill, and they uncover so many resolvable issues, bringing us closer together. When we are making decisions about our budget, curriculum, staffing, etc., we each bring different perspectives, misconceptions, and blindspots to the table. Were it not for our lengthy discussions, small issues could have the potential to grow into something more toxic and hurt our community.

The school culture borne of these disagreements is one of trust. Not blind trust, but the kind of trust where I know if a colleague disagrees with my decisions I’ll hear about it, and vice versa. This trust helps when working with students, as we feel comfortable advocating for their needs and we have the autonomy to make curricular decisions in their best interest. It’s always a work in progress; this past spring we addressed how the implementation of schoolwide decisions had impacted students’ learning, an uncomfortable conversation that helped us put the issue in the spotlight for the coming school year.

An interesting dynamic

Recently, a third grader from my friend and colleague Cleata’s class said to me, “I love how you and Ms. Cleata argue all the time, but then you eat lunch together every day. It’s an interesting dynamic.” As a staff we spend so much time debating with each other it’s easy to overlook how much the students pick up on this culture of healthy disagreement. Students at Mission Hill know that not all adults agree with each other, just as not all children agree with each other or with adults. Most importantly, our students recognize that disagreement is not the end of a conversation but the beginning of one. We are proud of this opportunity to educate students to move toward a more democratic society.

As the teacher-powered schools movement spreads, teachers will have the opportunity to craft their own school community in which students can grow and thrive. A crucial element in these school communities is that everyone, from the principal to the new student teacher, feels empowered to voice their disagreement. For with disagreement comes discussion, understanding, and, ultimately, trust. Well worth the time.

An earlier version of Danny’s post was previously posted on our blog. It has been re-posted as part of a series, “The power of Teacher-Powered Schools to create engaged citizens.”

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP