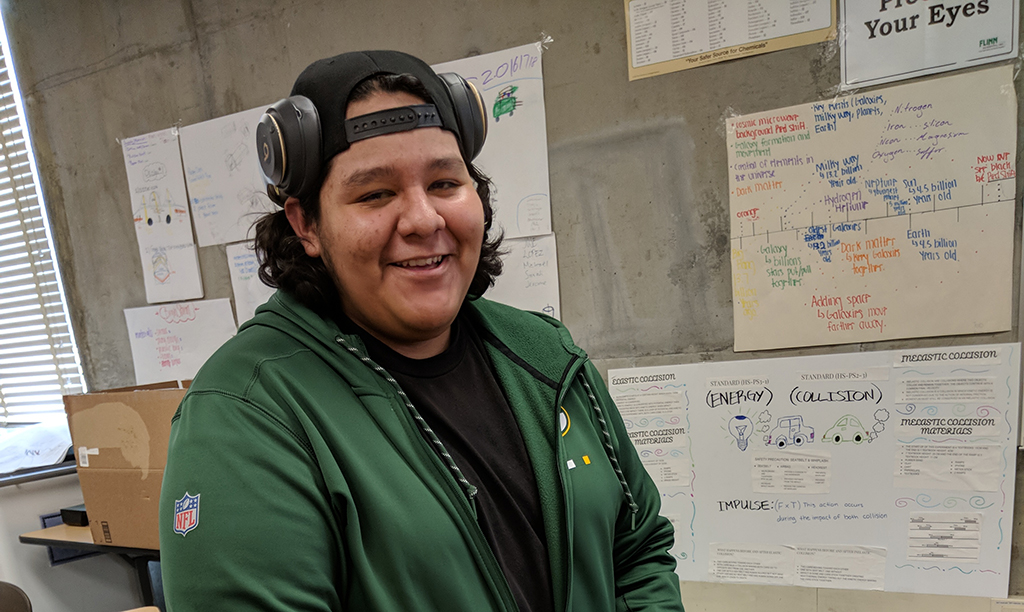

If you asked Hermilo—a former student at the School of Social Justice—what he was proudest of, he would tell you that it was the fact that he would be the first man in his family to finish high school and go to college. And he would make that distinction. Man.

And you would wonder why, for a moment, only to hear him later explain that women in his family had already finished high school and gone to college. They had already began careers in medicine with he soon to follow—leaving behind fathers and uncles in graves that were made too soon, in stories that ended too quickly, and in futures that never came to be. Where Hermilo was raised, men were quick to succumb to the coercion of gangs, drugs, and violence. Breaking that cycle for Latino men is important to Hermilo, something those who know him understand well.

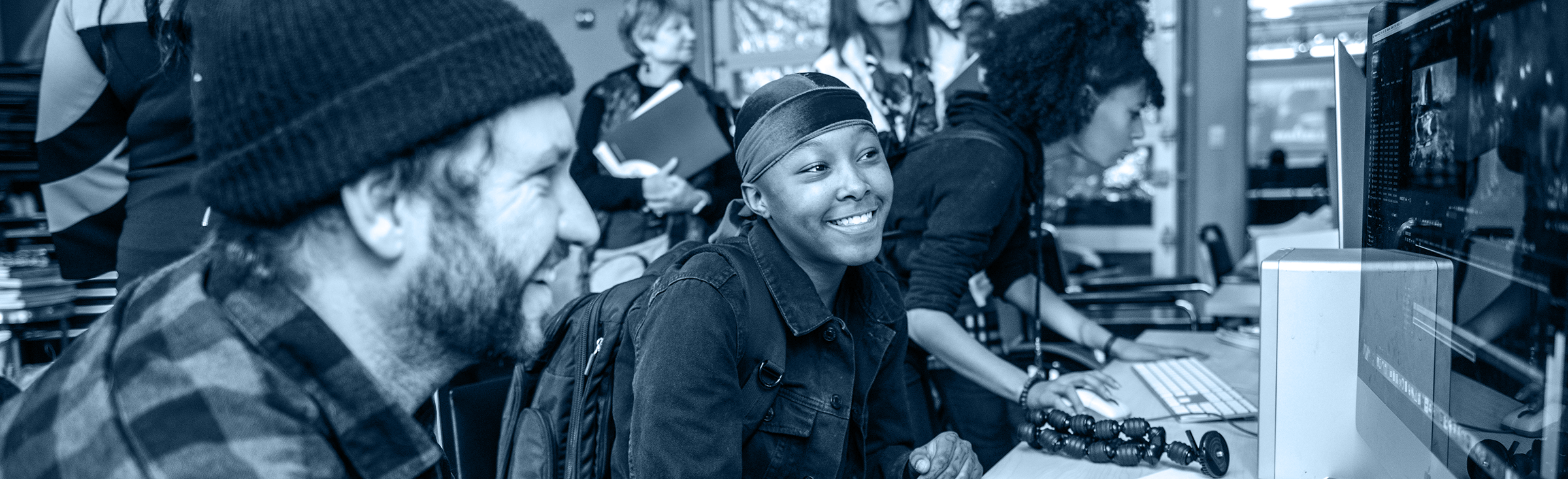

There are a lot of ways I could describe a student like Hermilo, but the best way to describe him justly is to tell where you might find him throughout a typical week. During lunch, it would probably be in my room. He would either be improving our STEM club’s remote-controlled cars, preparing them for data tests and race events. After school, it would probably be on the football field with his varsity team, or in Mr. Hwami’s room for tutoring in AP Calculus. During the school day, he would probably be sat toward the middle of the class—attempting to multitask between classwork, writing an essay, and researching college admission requirements on his phone. And on the weekends, it would probably be in a UCLA lecture hall to prepare for AP tests, or on the hour-long bus ride to get from downtown Los Angeles to the university campus. At any given time, he might be working on his service learning project.

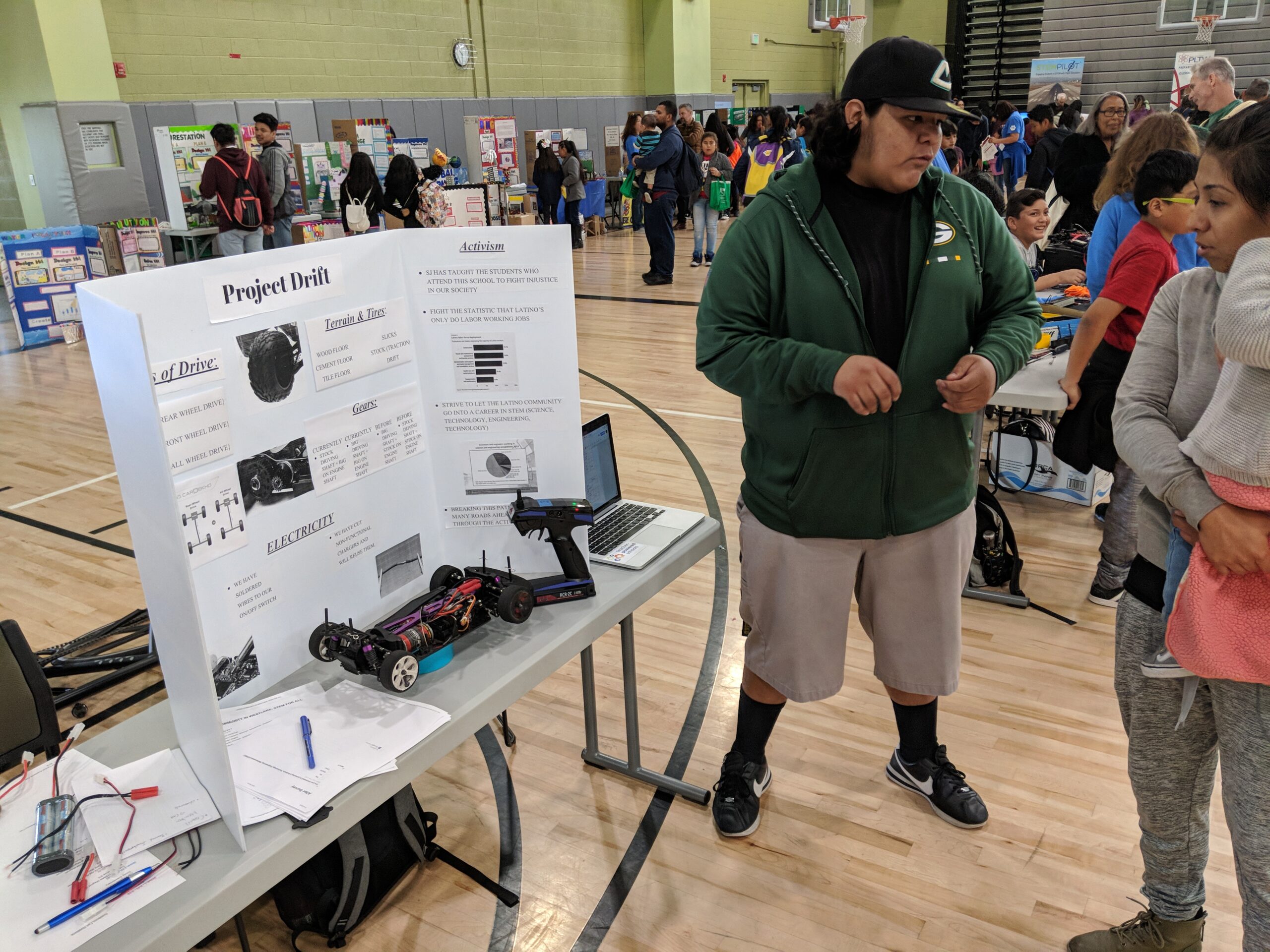

His project encouraged young Latino students to pursue careers in STEM. Hermilo found a calling upon hearing about the underrepresentation of Latinos in STEM fields and the overwhelming amount of Latinos in labor-related positions. And it was based on this discrepancy that he advocated for his community—and other communities of young people—to pursue engineering by teaching them about remote-controlled cars. Not only did he give students the experience to play with the cars, he also provided a fundamental understanding of the physics involved. The students would get to see firsthand how a gear ratio affects your turning and speed, or how the electrical channels affect the signal that the remote receives. They would get to see how tire treads affect the friction on different surfaces and how scientific data is collected through multiple trials.

As I watched Hermilo walk the stage in his graduation gown this past spring, I reminisced on his time at the School of Social Justice. I remembered his diligence and dedication. I remembered his willingness to get his hands dirty in science experiments. I remembered his commitment to proving people wrong, subverting expectations.

That’s a major consideration in our school’s design—to subvert the stereotypes that we have been placed in, and it is a design that both students and teachers participate in creating. Through our humanities classes, teachers establish the spaces to understand the climate of our society. These classes explore everything from the upbringing and ancestry of our students, to the issues that our society faces today. In one classroom, you might see students writing poetry about themselves inspired by George Ella Lyon’s “Where I’m From.” In another classroom, you might see students engaged in socratic discussion over homophobia, sexism, or racism. Where both these classes will end, though, is with a service learning project. A project where students get the opportunity to take their knowledge and give back to their community by changing minds, inspiring action, or providing useful information.

It wasn’t always like this in the Belmont community where the School of Social Justice is located. In fact, it was only 2006 when the school opened as one of the first small learning communities in Westlake, Los Angeles. Around this time, conversation began about specializing schools to fit student needs and address concerns regarding facilities and class sizes. Among the schools that were established around fields like medicine, business, visual arts, and many more focus areas, was the School of Social Justice—one of four schools built on the Miguel Contreras Learning Complex. Years later, these four schools would become four of the district’s 32 high school pilot schools, which are research-based, student-centered schools that serve as a model of educational innovation.

There’s much that can be said about how having teacher-powered autonomy has allowed our staff to innovate our school program, but even more can be said about how students have been able to innovate our school as well. Teacher-powered autonomy enables the teacher team to create the conditions in which our students thrive. Which brings me back to Hermilo. His service learning project was an example of that success, that innovation. Over the course of several months, Hermilo presented at local fairs in different communities of color on engineering concepts, carrying around his trifold board and his toolbox full of equipment. He catered his presentation to different audiences from elementary, to junior high, to high school students, and even to parents. Their eyes would light up as their hands touched the remotes and their smiles would widen as they would open up the cars for the first time.

And as he taught his community, I realized that there was something far more salient to his service than the words he said. Hermilo stood as the living embodiment of what he wanted students from our community to be. He wanted them to be the next experimenters and inquirers. The next engineers and innovators. He wanted them to see past the barriers that have long prevented communities of color from reaching careers in science and see the sciences as something they could be part of. He wanted them to imagine a world where young Latino men could feel as proud as he did—in futures that have been made all the better through passion, access, and education.

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP