“In order to protect Americans, the United States must ensure that those admitted to this country do not bear hostile attitudes toward it and its founding principles… the entry of more than 50,000 refugees in fiscal year 2017 would be detrimental to the interests of the United States”- Executive Order 13769, signed January 27, 2017.

Did I read that correctly? “In order to protect Americans,” we are going to keep out people who are fleeing danger and persecution? As a social justice-minded teacher in a social justice-oriented school, it didn’t sit right with me that so much harm was being done to some of our most vulnerable, on the national stage no less, and there was little being done about it. Worse, there was little being taught about it! How can we have an informed conversation as a citizenry if so few of us know about the experiences of refugees?

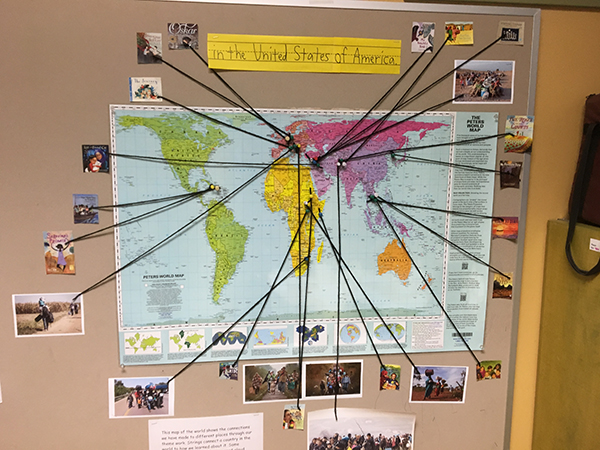

I decided to start close to home, which meant exploring this topic with my students in our fall social studies theme. At Mission Hill K-8 School we use our curriculum autonomy as a Boston pilot school to learn about science and social studies through three in-depth themes per year. Our fall 2017 theme was “The Peopling of the United States”, and under that umbrella I wanted my class to study the refugee resettlement process. This in itself presented a problem: I teach a multiage class of 1st and 2nd graders, within an inclusive and socioeconomically diverse classroom.

Over the summer I searched for teaching resources concerning refugees which could be applicable or accessible to 6, 7, and 8 year-olds, and if those resources are out there, they’re very well hidden. I attributed the limited availability of resources to the popular view that young students are unable to think about and discuss complicated or polarizing issues, and I continued with my plans full steam ahead. Luckily, the United Kingdom has some wonderful resources for teaching about refugees with younger students, and I also read several books about the experiences of refugees; I didn’t want our learning to lose sight of the human element by getting bogged down in facts and figures.

Over the summer I searched for teaching resources concerning refugees which could be applicable or accessible to 6, 7, and 8 year-olds, and if those resources are out there, they’re very well hidden. I attributed the limited availability of resources to the popular view that young students are unable to think about and discuss complicated or polarizing issues, and I continued with my plans full steam ahead. Luckily, the United Kingdom has some wonderful resources for teaching about refugees with younger students, and I also read several books about the experiences of refugees; I didn’t want our learning to lose sight of the human element by getting bogged down in facts and figures.

The emotional component of our theme didn’t hit me until August, a month before starting; I had just read A Hope More Powerful Than the Sea by Melissa Fleming, a stunningly beautiful yet painful account of Doaa al Zamel’s journey to safety. How could I have a holistic and deep conversation about the experiences of refugees with my students while acknowledging the pain and loss which is a part of this journey for so many, while maintaining a safe and positive learning environment for young children, engaging my students in meaningful project work, and keeping families in the loop for a theme that is highly controversial?

Luckily, working at the teacher-powered Mission Hill School has its benefits, one of which being our curriculum shares. As a team of teachers, we come together before the start of each schoolwide theme to review each other’s curricula and provide feedback. My colleagues acknowledged my concerns about doing this complex theme justice while affirming that my students are not too young to grapple with complicated issues like refugee resettlement. Before the theme began, I sent home a letter to keep families connected and invite conversation. One of the parents in my classroom not only responded positively, but she also was an invaluable resource for ways to bring art and theatre into our work.

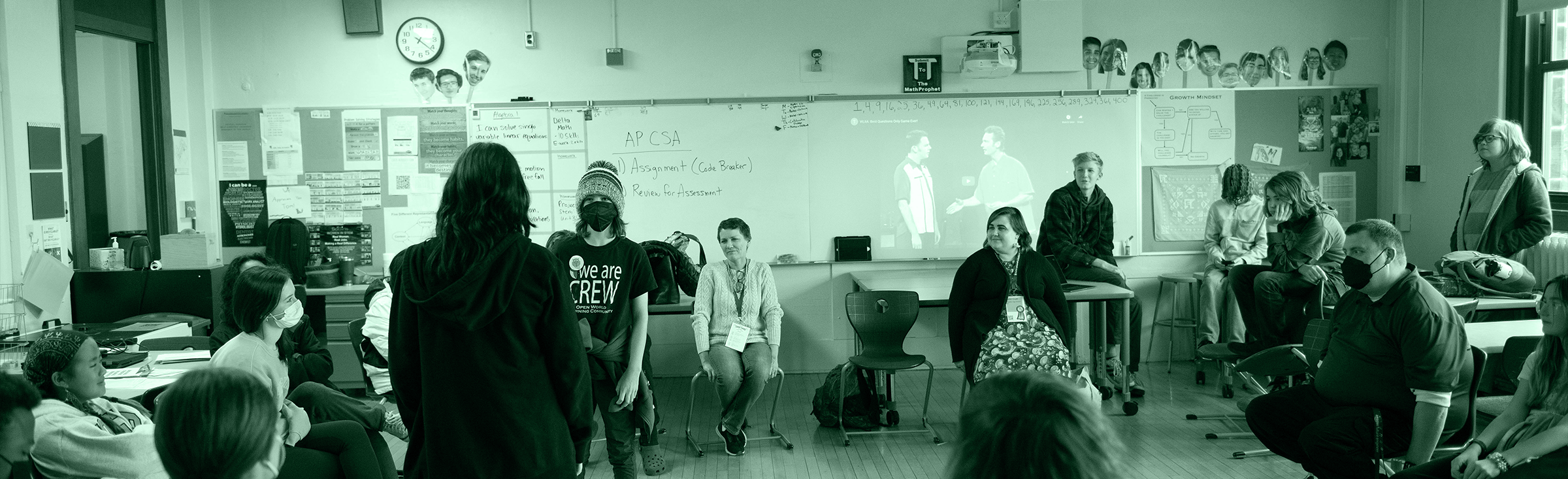

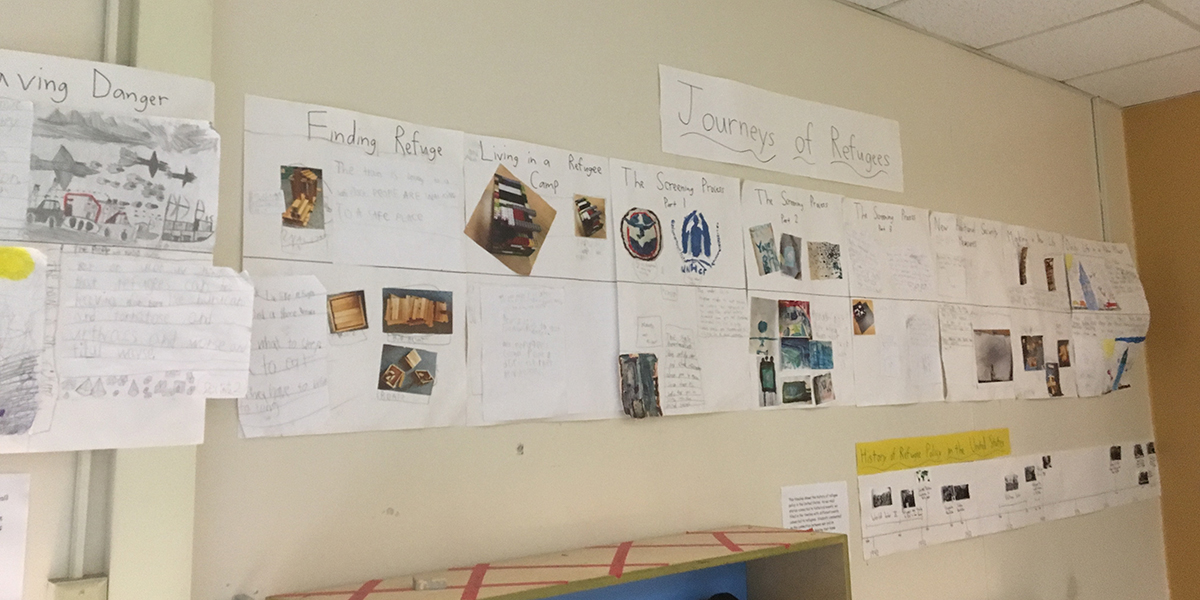

Across the three months in which we studied refugees, our collective learning went far beyond my greatest expectations. Students wrote passionate paragraphs about their thoughts on whether or not refugees should be able to come to the United States. There were many happy tears at the conclusion of Lost and Found Cat, The True Story of Kunkush’s Incredible Journey by Doug Kuntz and Amy Shrodes, in which a cat living with a family of refugees is separated from and later reunited with his family. I noticed colleagues including refugees in their study as our class’ work was talked about in the larger school community. I received nothing but positive feedback from parents, with one describing our moving panorama of the refugee resettlement process as “absolutely incredible.” One of my students reflected that “it’s very, very hard to get into the United States as a refugee” while another stated correctly that “more than half of all refugees are kids.” In a testament to how much the theme stuck with her, one of my students took out a book we had read about a refugee out of the library months after our theme ended.

To date this is my favorite theme I have ever taught at Mission Hill School, and I strongly believe that the autonomy I have as a teacher was key to making the curriculum successful. Mission Hill School is a pilot school within Boston Public Schools, a designation which provides us with the autonomy to try new and different ways of teaching and learning. Specifically, our school has autonomy over our budget, calendar, curriculum, staffing, and governance.

In this case, we have the freedom to decide our school-wide themes as a staff, and the individual autonomy to design what this looks like in our classrooms. These autonomies allow us to meet the needs of our students as best as we can; something all schools should be afforded. Thankfully we are not alone—there are other schools across the country which are also teacher-powered and have the autonomy to make decisions such as these, each emphasizing what is best for their community of learners.

The autonomy I have over what I teach, allowing me to design my own curriculum, made this possible. The collaboration I have with my coworkers, getting feedback and advice to help strengthen my plans, made this possible. The fact that no one was kicking down my door to stop me teaching about refugees but instead was knocking on my door to help me made this possible. In preparing and teaching this theme I felt trusted, I felt empowered, and I felt driven to do my best work. What would our nation’s schools be like if every teacher felt this way in their classroom?

Danny Flannery is a 1st/2nd grade teacher at Mission Hill School in Boston, MA. He is also a Teacher-Powered Ambassador.

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP

NEWSLETTER SIGN-UP