The GCSE marking fiasco and the continuing foundation of academy schools has one again put autonomy and accountability in the spotlight.

Yet it's worth remembering that these are not only very English obsessions, but relatively deep-seated in our history. "Our concern has been with accountability and autonomy – not as alternatives, but as significant and meaningful concepts which need to be better understood in relation to each other, having regard to specific organisational settings," is a sentence which could have appeared in the 2010 schools white paper.

In fact, it dates from the 1975 report of the annual Belmas (British Educational Leadership, Management and Administration Society) conference, which will be revisited during Looking Back to Look Forward, a 40th anniversary event to be held in Birmingham on 21 November.

In some ways it's surprising to find that the debate about autonomy and accountability was active nearly 40 years ago, developing into what has become a policy-makers' preoccupation. Anita Ellis, deputy head of Hartcliffe school in Bristol, told the 1975 conference that secondary heads in England had much more autonomy than their US or French counterparts, and suggested there was an unwillingness to acknowledge this for fear of stimulating fresh accountability measures.

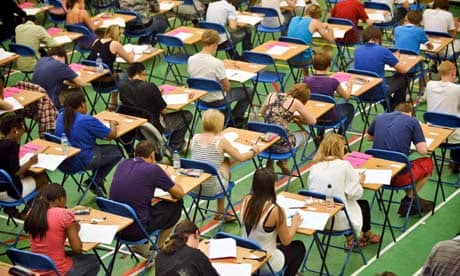

In her view the accountability of teachers and schools had for a long time essentially rested on the exam results they secured. Many would argue that this is even more strongly the case today.

No-one at the conference seriously advocated that there should be no accountability. The challenge was to find a format that promoted rather than inhibited educational aims.

The push for schools to achieve greater autonomy was developed and driven by a right-wing group of Conservative MPs and led to the 1988 Education Reform Act. This increased schools' power over resource allocation but introduced a prescriptive and detailed national curriculum and regular pupil assessment, with Ofsted and league tables emerging four years later.

Former education secretary Baroness Shirley Williams commented in 2009 that it represented "a lurch from one extreme to the other, from too much autonomy to virtually none. It is the heavy price England pays for a highly politicised system."

The rhetoric and the reality

Despite the growing power of central government, the dominant rhetoric has been about autonomy, independence and liberation from bureaucracy (read local authorities) and this focus has persisted and grown stronger over the years. The driving factors behind this include the commitment to free market ideology, England's highly centralist constitution, and the symbolic power of the elite independent school sector.

And paradoxically, despite the persistent and growing emphasis on autonomy, most school practitioners consider themselves constrained by government requirements to a far greater extent than their forbears in 1975. Schools have many more responsibilities and the centre has been transformed from a trusting referee and resource provider to a demanding and impatient managing director with frequently changing identities and priorities.

Moreover, performance using international benchmarks has been variable – particularly in relation to equity. It is striking that systems with better educational outcomes, such as Finland, often have considerably less demanding forms of accountability and the top-performing countries don't generally use autonomy as a dominant driver of improvement.

The biggest change since 1975 has been the progressive disempowerment of the intermediate tier of governance which international research has shown is a vital element in system improvement. This looks likely to result in a highly unstable framework, marginalising the community and local dimensions.

Unsurprisingly, many schools appear to find the stand alone model uncomfortable and are clustering together in various groupings such as academy chains and co-operative trusts. From the point of view of pupils and their families, the likely collapse of any local strategic co-ordination and community governance could have serious consequences and raises major questions about democratic legitimacy.

A key challenge in the next few years will be to create an effective and legitimate multi-level system of educational governance that is fit for purpose and can command the trust of the public and the profession.

This requires addressing a question that is as crucial and unresolved now as it was in 1975, and which has become even more pressing: "To whom should schools funded by the public purse belong?"

Ron Glatter is emeritus professor of educational administration and management at The Open University and Susan Young is a freelance education journalist

For further details about the conference, see www.belmas.org.uk

This content is brought to you by Guardian Professional. Sign up to the Guardian Teacher Network to get access to more than 100,000 pages of teaching resources and join our growing community. Looking for your next role? See our Guardian jobs for schools site for thousands of the latest teaching, leadership and support jobs

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion